Introduction

We have all probably said to ourselves when performing a conditioning session, "I will do this for X amount of time or do these intervals for X amount of time." On the other hand, we have also said to ourselves when performing a weight room session, "I will do this exercise for X repetitions."

Why are we only prescribing duration for conditioning and not for exercises?

Both prepare an athlete to compete in sport, so why do we differentiate between the two?

They should not be considered separate entities because all qualities can be developed using both scenarios, especially when preparing an athlete from an energy system profile perspective.

RECENT: Shift from Block to Vertical Integration for In-Season Program Design

Sport is timed by duration, not by the number of repetitions, so using timed sets for the weight room makes much more sense if we are trying to develop training programs specific to the demands of sport.

On top of that, utilizing time will control for the possible variance in training volumes amongst your athletes and is the best method to develop repeat sprint ability.

Energy System Basics

Before we continue with the practical application and reasoning for timing your sets, we want to touch back on what we wrote in the first paragraph, "Sport is timed by duration, not by the number of repetitions."

When training athletes on the field or in the weight room, we look to develop three energy systems: the oxidative system, the lactic system, and the alactic system. Each plays an important role in the complete development of every athlete.

In the following paragraphs, we will relate each energy system to a different sport for simplicity's sake.

Oxidative System

The oxidative system can be thought of as the energy system a cross country runner primarily relies upon in their sport. The duration of their events is typically 15 or more minutes, and the efforts performed during their events are of a consistent, sustained nature. The oxidative system takes over energy demands in any activity lasting more than three minutes in a sport with continuous work, gradually relying more on fat as a fuel than carbohydrates as the event goes on.

Lactic System

The lactic system is what a hockey player primarily relies on for energy demands because a shift in hockey lasts roughly 45 seconds and is performed at a moderate-high intensity.

The lactic system is primarily responsible for providing energy for moderate to high-intensity efforts lasting over ten seconds and up to three minutes. The aerobic system cannot provide enough energy fast enough for these bouts, so the lactic system relies more on carbs than fats.

Alactic System

The alactic system is what a sport like American Football primarily relies on because most plays last less than ten seconds and are always performed at maximal effort. The alactic system can only supply these maximal outputs because immediate, available energy from PCr is required to fuel them.

Energy System Pyramid

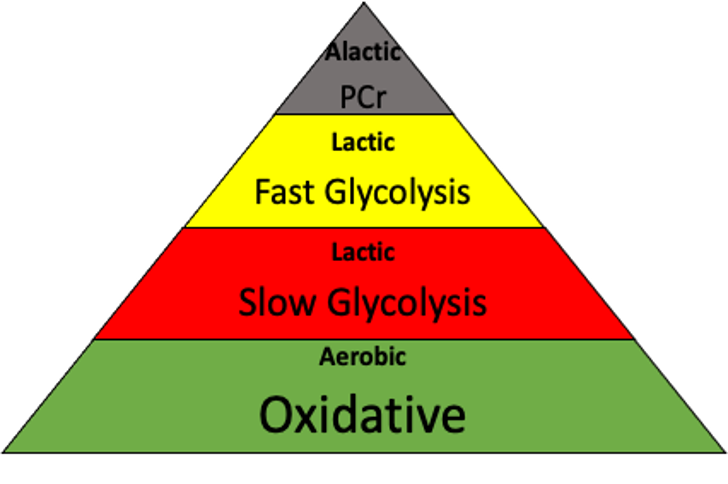

Figure 1 demonstrates how the energy systems are tied together. Like any pyramid, the first step is creating a wide base. The wider the base, the higher the peak.

The base is the oxidative system because it is what gives us the ability to train more frequently at higher volumes and helps us recover from training. It's an important first step to develop before going forward because having the ability to train and recover from more volume gives you the ability to make stronger adaptations.

The next pyramid level is the lactic energy system, which is the moderate-intensity/moderate-duration effort. We won't elaborate much on this topic, but generally speaking, sport covers this base with the way practices are performed. The stop-and-go nature of practice and learning of new strategies/skills results in moderate-intensity efforts with incomplete rest.

The peak of the pyramid is the alactic system. This may be the most important box to check in your training because it is difficult to accomplish in practice with any team sport. It has the largest carry-over to high performance in most sports. Due to how much skill and strategy are required in sport, most efforts aren't truly maximal because you have to be conscious of many other factors.

The beauty of sport performance within a weight room is that it allows the athletes to give maximal effort during low-skill movements (such as linear sprints, trap bar deadlifts, or bench press). In this way, the alactic system can be trained very effectively to raise the athletes' overall athletic ceiling. We perform training like this to raise our ceiling with this physical quality.

In sport, one of the largest factors that decide who will come out on top at the end of a competition is which team can perform high-effort sprints (bouts) over and over. This feat is especially important at the end of the game when fatigue becomes a larger factor. It's often referred to as repeated sprint ability—one of the main adaptations we all hope to develop with our athletes.

Maximizing Training Density

As we have mentioned, success in sport comes from producing max efforts repeatedly throughout an entire competition. For an athlete to be able to accomplish this, there are some primary prerequisites they must develop during their training in the off-season:

- Develop their oxidative system and ability to perform/recover from large amounts of low-intensity work.

- Improve the ability to shuttle blood around the body to induce metabolite removal and efficient recovery.

- Improve their ability to display alactic max outputs by training high-intensity exercises with adequate rest to ensure the training was quality- and not quantity-based.

Once these prerequisites are developed, the outcome is an athlete who can train both very hard for short periods of time and also train for a very long time at low intensities. The goal then is to combine these two qualities into one by developing an athlete that can train very hard for short periods over and over again.

The easiest way to develop an athlete with this ability is to set up every training session, including the weight room, like something with an underlying conditioning goal. The underlying conditioning goal in the weight room is to improve the training density that the athlete can tolerate. Training density is the number of sets and repetitions performed within a certain time frame. If we improve this number with our athletes weekly and keep the quality of the training high, then we are destined to prepare the athletes for their sport.

Repeat Sprint Ability

In team sports, the deciding factor in competition is a team's ability to perform high-quality repeat sprints throughout a game, especially as it comes to an end. To clarify, when we talk about repeat sprint ability, we aren't only referring to sprinting but to any high-intensity effort that may take place, like swinging a bat, jumping to spike a volleyball, or driving into a defender you are intending to block.

Given the versatility of repeat sprint ability, one might think of it more as repeat max output ability. For the sake of this article, a max output is an effort of up to 10 seconds, which means we are referring to the alactic system (peak of the pyramid) that we discussed earlier.

This is essential for team sport because many crucial moments occur during a game that goes far beyond just sprinting in a straight line. That is why we have found it so important to develop a style of training that will prepare an athlete holistically for performing max outputs with their entire body. Also, performing sprints is probably the best way to improve this ability, but when athletes are already running so much in their sport, it may not be the smartest way to train it. In addition, it will likely not provide enough volume to fully develop this quality. We have resorted to using timed sets in the weight room to further develop this adaptation.

Why Use Timed Sets in the Weight Room

The most common prescription for volume in the weight room is repetitions. Repetitions were established to make it easier for everyone to understand and apply exercise volume to the masses. Instead of utilizing seconds, people argued that it was easier to describe with repetitions, which in reality is easier because nobody wants to have to stare at a clock or timer or count out loud to themselves or to their partner during every set they perform.

Using repetitions allows everyone to be on their own clock and work at their own pace. Allow each individual to allot as much time as they want between reps during the isometric or "resting" portion of the movement and make each rep last as long as they want. One of the many incidents we have seen in the weight room relating to this issue is an athlete going for a heavy five on a squat and resting five-10 seconds between reps to grind out another slow, choppy rep. Therefore, a set that should last roughly 20 seconds lasts up to a minute.

Using reps is perfectly fine for an individual training on their own or someone getting trained with no specific goals or needs. This is the case if the individual just wants to feel like they had a "good" workout, making it the practical thing for them to do. This is not the case for individual athletes with specific goals or athletes in a team setting with specific goals.

If we want the training programs we have created to be as effective as possible, we need execution as specific as possible for the individual/team goals or needs. If we are not exactly sure of what training our athletes have completed, we cannot understand the effect our training program had on our athlete's performance. This makes it challenging to decipher which part of the program played a role in the changes in post-test and retest with our athletes.

We have found using timed sets for most exercises in the weight room to be the most effective means of exercise prescription. It makes sure all athletes are given the same stimulus. Going back to what we mentioned above, five reps for one athlete may be taxing a completely different energy system than another athlete if their intent towards their exercises is much different.

Keeping set duration uniform for all athletes removes many common faults that take place in the weight room like:

- Individuals of different sizes who have vastly different ranges of motion for movements.

- Individuals who rush through sets to get done as fast as possible.

- Weight room heroes who grind out and go as heavy as possible every set.

- Athletes getting through workouts at different speeds.

Weight Room Timed Sets: Maximize Repeat Sprint Ability

When training repeat sprint ability, the goal is to keep intensity as high as possible for sets that last between five to 10 seconds to develop the alactic energy system. This is difficult to prescribe using repetitions as our metric for volume. For example, as mentioned before, prescribing three to four repetitions to the athletes can lead to many different outcomes. One athlete may complete the work in six to eight seconds, while it takes around 15 seconds for another athlete. This means that different athletes will train two different energy systems for the same set during the same workout, so the stimulus is not uniform amongst all of your athletes. To understand the program's effect on the athletes, we have to ensure that the intended quality is being trained.

In our experience, prescribing volume through time instead of repetitions increases the repeat sprint ability of a team. The focus of each set shifts from moving as much load as possible for the prescribed repetitions to moving the prescribed weight at the fastest rate possible for the prescribed time domain.

To control the rate of movement during the timed sets, we use different percentages based on our goal for the training. The idea behind using percentages in a timed set system is to control the rate of movement during the set by adjusting the weight in use for each set. However, this only works if the athlete consistently applies max intent to every set. Therefore, regardless of load, they try to move the weight as fast as possible. Naturally, it causes the athlete to move faster or slower, depending on the percentage.

The only issue with using the load to control the rate of movement is the exercises you choose to use to improve repeat sprint ability must be mastered from a technical standpoint by the athlete.

When we program exercises for the purpose of improving repeat sprint ability, we normally select ones that are simple to execute and can be performed by a wide variety of athletes. Therefore, athletes don't have to learn another complex skill in addition to their sport skills. This minimizes the need for making individual variations in the workout. Also, suppose it takes the athletes an extended time to learn how to perform the exercise. In that case, we are going to be wasting the majority of our off-season teaching movements that are difficult to execute, instead of using ones that can be performed by a wide variety of athletes that will lead to adaptations at a faster rate.

Another benefit of performing the majority of your repeat sprint training in the weight room using timed sets is you can apply it to more than just the lower body. It can be applied to all the major movement patterns or muscle groups if you can select the correct exercises that can be performed with max intent safely.

Lastly, we have found this type of training to be most important for more veteran athletes with higher training ages who are likely already strong enough and need to focus on other training qualities. The other qualities are power, speed, and repeat sprint capacity.

Timed Sets Practical Application

If we take a look at the duration of each energy system, they are primarily working over a specific period of time. For example, the alactic system is dominant from one to 10 seconds.

How do we determine the length of the set?

We like to categorize it into two categories: either quality or capacity focus. If the purpose of the exercise is to perform high-quality repetitions, perform the exercise at the bottom range of the time frame. If the purpose of the exercise is to build capacity, perform the exercise at the top range of the time frame. However, if you have a well-balanced athlete, you would probably have them go somewhere in the middle of the time frame or have them focus on each during different days each week.

How do we apply energy system training to a workout?

First, we decide what the main goal is for the workout of the day. Is it to improve speed or increase the tolerance to lactate (which energy system is primarily responsible)? Second, we identify if the athlete needs to improve high-quality repetitions (power) or if the athlete needs to improve capacity (conditioning) in that particular energy system. Third, we decide which exercise to which we will apply the specific energy system training, which is dependent on the goal of the exercise.

Understanding the purpose of each exercise is essential for designing a proper program.

What are some exercises where you can implement a timed set?

Below is a list of a few exercises where we successfully implemented timed sets. These are just some examples because we don't want to leave you hanging, and we want you to experiment on your own. We have also included two complexes that train the alactic system to demonstrate how you can combine timed sets with repetitions sets.

Exercises to implement timed sets:

- Step Up

- Hip Thrust

- Trap Bar Deadlift

- Bench Press

- Lat Pulldown

- Chest Supported Dumbbell Row

Combining timed sets with reps:

1A) Squat x10s

1B) Box Jumps x4

2A) Bench Press x10s

2B) MB Throw x4

Conclusion

A few of you might be skeptical of this approach because you have always used repetitions for keeping track of volume. Remember, sport is timed by duration, not by the number of repetitions. By timing your sets, athletes get different amounts of volume during a workout depending on how well trained they are. You could even argue that timed sets are a more individualized approach. Most importantly, timed sets will increase repeat sprint ability—crucial in sport due to the high-intensity bouts.

We hope that you have learned something new and when you have processed this new information, start to implement timed sets.

Co-authored by Jesper Mårtensson

Regan Quaal is the Assistant Sports Performance Coach at the University of Minnesota with Cal Dietz.

Jesper Mårtensson is pursuing his M.Ed. in Sport and Exercise Science at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. He is a Sport Performance Coach intern at the University of Minnesota supervised by Cal Dietz.