I’ve recently started getting more questions about conditioning for athletes. In the collegiate setting, I didn’t have to worry too much about this aspect because the sports coaches usually wanted to handle this. God forbid we get too far away from sport-specific agility drills for a few weeks. With this rationale, more than 90 percent of athletes were on the “over-volumizing running in the wrong energy zones” team that I never heard about.

This article will outline a few options for the various lanes of conditioning and how you should set them up. The object of these conditioning options is to develop the primary energy systems of your given sport without running all the time. Someone just posted a study about how the constant travel basketball culture is starting to have a negative effect on the athletes… You don’t say! No wonder these 19- to 22-year-old guys walk around like they’re 80 years old. It’s because they run long distances and do change of direction in a competitive environment almost all year long with minimal strength training.

RECENT: 8-Weeks-Til-Camp Summer Program for High School Football

We’re getting to a point where the strength work is needed just for the athletes to survive their sports instead of improving performance. If your rationale is “Well, they have to be able to endure that type of stimulus,” you are just adding to the problem. If you get a chance to get them away from this stimulus, DO IT. If it’s a weight room sin to load dysfunction, then why is it OK to continue to stack high-intensity change of direction and sprint work on these athletes when they should be getting a break from that?

These options are meant to keep them in the ballpark of being in game shape without beating the crap out of them. They don’t have to be ready all the time; just ready to get ready. So, if you read these and think they are not sport-specific enough or intense enough, that’s why. These could be considered GPP conditioning options.

Many of the questions I get are related to when to do each type of conditioning. If you have the luxury of splitting the sessions up by a few hours, that would be my first choice. Many of us don’t have that option. Let’s be realistic.

I’ve always had success and thought it made the most sense to do alactic work (short-burst work) before the lower body lifting days and the lower intensity/longer duration work after your upper body lifts in the off-season. How many of you winced a little bit when I said lower intensity? Relax, this shit really works. We can’t max out every time we’re in the weight room, so you can’t go full blast on all you’re conditioning all the time, either.

What’s your priority? A lot of people have a hard time backing off of the volume and intensity of anything when it comes to strength and conditioning. When I say most people, I’m talking about sports coaches — usually the strength coach knows better.

The reason I say this is not to be a wise-ass — OK, mostly not to be a wise-ass. The main reason I state this is because many of you answer to these people and are probably going to have to sell this idea to them. How you do that is up to you. Sorry, I don’t know the coach you work for or what makes them tick. Maybe you can go with the old “Hey, I was watching a clip on LeBron this weekend, and he was doing this stuff.” They try that shit on you; maybe it will work on them? Whatever you do, don’t open with “I saw this in an article from Nate Harvey…” That will probably get you nowhere fast.

We have to step back and see what this time of the year needs to be dedicated to. Getting strong takes years of hard work, but you can get in shape in a couple of months. If you are trying to make progress on the strength front while running your kids into the ground year-round, you’re just going to waste your time. You can only serve so many masters.

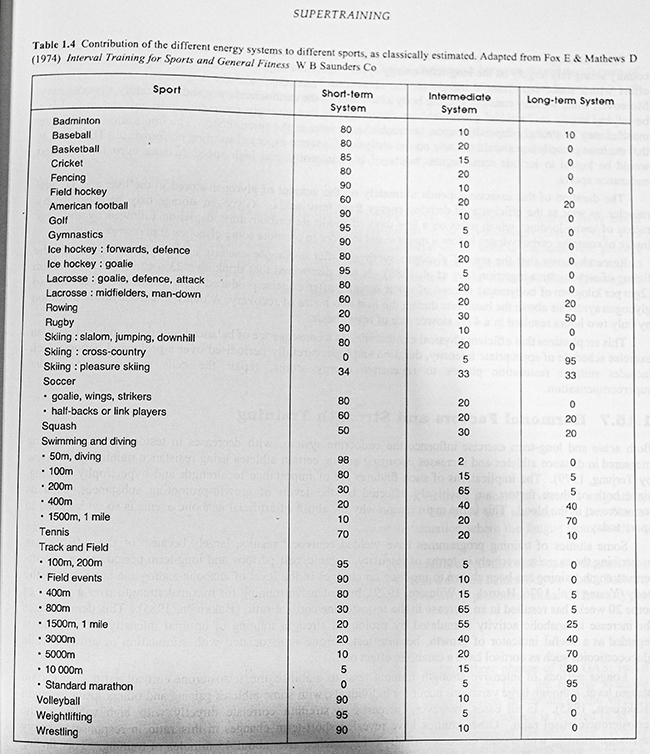

Below is a chart from Supertraining. It breaks down to what extent the energy systems are used in various sports. Yes, we could debate the actual percentages used for each sport. The main point is to look at how little is actually dependent on glycolysis (intermediate system).

Even though we know better, how much conditioning turns into a lactic acid bath? Yes, in most sports, you have to, at some point, tolerate some lactic acid, but the majority of the time, you do not. The more you operate in this intermediate system, the more you will produce excess hydrogen ions, which are the real culprits for muscle fatigue. These hydrogen ions are cleared by oxygen. If we improve our oxidative system, we can recover more quickly and efficiently between bursts.

This is why the intermediate system was affectionately deemed the “zone of shit” by one of my former supervisors. Everyone wants to train there, but a very small percentage of any sport is performed there!

Conditioning options for Lower Body Days (short-term energy system) to be done after a thorough warm-up prior to lifting

- Sprints lasting 12 seconds or less with 1- to 1.5-minute rests

Variations:

- Hill Sprint

- Sled Sprint

- Partner resisted sprint

Various starts:

- Turn and sprint: face perpendicular to sprint path, turn, sprint

- Lying turn and sprint: face perpendicular to sprint path, turn, sprint

- From stomach

- Chasing partner from stomach

- Continuous Bounding

- Repetitive Horizontal Jumps

Volume Suggestions:

- Start at 5-8 sprints

- Add 2 each week

- Change exercise every 4th week

- Week 4: drop volume down slightly

- Week 3 = 12 sprints; Week 4 = 8-10 sprints

Conditioning options for Upper Body Days (long-term system) to be done after upper body lifting

- Continuous activity for 20-40 minutes

- Heart rate: 110-130

- Semi-hard breathing, somewhat hard to carry on a conversation

- No lactic acid should be present

Variations:

- Light Sled Drag Walks: multi-directional

- Light Sled Drag Walks with light shoulder dumbbell or band work while dragging

Long Duration Medicine Ball Throws:

- Throw for height, walk 10 yards and back, throw – repeat

- Throw for distance, backward walk/jog to ball – repeat

- Mix in various track warm-up drills with the throws done on turf with no shoes on

Weak Link Circuit: Identify weak body parts, set up stations to do low weight high rep work. Jog/walk/track warm-up movement to next station –repeat

Overhead Medicine Ball Throw Technique: These extensive throws are a great tool to integrate triple extension, reactive ability in the hips, teach proper knee movement during squatting, and will help develop your oxidative system. I implemented them with the basketball teams and saw great improvement in their squatting proficiency. It forces them to open their knees and use their hips if you teach it right. Over the course of a few weeks, they will get a ton of reps to help reinforce proper hip recruitment.

Cues:

- Roll your knees out

- Butt back

- Finish tall

These are a few examples you can use to give your athletes a break while continuing to keep them in shape in the off-season. Give some of these a try and get some feedback from your indicator athletes next off-season.

I’m very confident your strength gains will benefit from these more than the typical sport-specific agility training we do all year long.