This particular part of the article series is by far the most provocative, and to some, will appear to take a negative tone. Please try to remain open-minded and understand the points I am trying to get across. These are major issues that are holding our profession back. These issues are a reality, and we need to face reality in order to start working toward solving problems.

RECENT: Strength and Conditioning is Failing: Our Relationship with Administration

History, State of Knowledge, and Commercialization of Training

Collegiate strength and conditioning has grown by leaps and bounds since Boyd Epley became the first collegiate strength and conditioning coach in 1969. Being as though our profession is less than 50 years old, it is essentially still in its infancy.

Unfortunately, this industry is so new, we don’t really know what we know and more importantly, what we don’t know. In the next 10 years, it is likely our knowledge will grow considerably, meaning that right now, we don’t really know that much. There is very little conclusive information in certain areas, which leads to disagreements between strength coaches on technique, periodization, daily planning, functional movement, etc. Multiple messages being delivered to administrators and sports coaches promotes the perception that we don’t know what we are doing, that it doesn’t matter what we do, because it is JUST lifting weights.

Many sports coaches do not understand the process, but just see athletes working out, and want them to do more and go harder. The result is an attraction to commercial fitness fads, Navy SEAL training, strongman training, etc. I do not have a problem with taking aspects from any of these categories, as long as it fits in the training process and has a precise reason for being used resulting in a specific outcome that correlates to the objective being sought. But, there is no reason to copy program X off of TV because the coach liked how he felt doing it. There is no good reason to have young athletes carry logs over their head just because it is the cool thing to do, or even for mental toughness, as some like to claim. What we are asking for is a lack of production, injuries, and possibly worse. These programs do not have a logical progression to what we are trying to achieve.

Commercially popular training is meant for only one thing, and that is to make money, not develop athletes. It is performed to make clients feel like they are doing something productive, but not to take them too far beyond their comfort zone. This keeps them coming back, meaning they are paying more money. If they are pushed too hard, they don’t come back. If they don’t do enough, they won’t come back. Training for sports typically needs to go beyond the comfort zone and should have specific objectives that require goal-specific training. The fact that the only specific goals commercialized programs have are to make money begs the question: Why we would even consider utilizing these methods with our athletes?

In what ways are yoga and Pilates adequate for developing an athlete? While it can be claimed that there are benefits that can be derived from these methods, it is quite arguable that there are methods that would yield similar results in much less time and do not require the use of a special instructor. If this is true, why are the former methods held in such high regard? The answer is simple: to the uneducated, it is easy to see something that looks appealing and gravitate toward that method since it is already laid out in a manner that can be easily reproduced. Having to put time and thought into something to figure out how to implement methods that do not come with an instructor or a video to follow would take too much time and effort.

The problem with all of this is that commercialized concepts are all that some sports coaches know. They have no awareness that there are more effective means of training with a much greater scientific rationale for their use, including greater benefits.

RELATED: GPP Training: You're Doing It Wrong

I have no problem with non-athletes performing any type of exercise that they enjoy doing. In fact, I recommend people finding what they like and putting effort into those things. But the efficacy of utilizing commercially popular programs, such as Zumba, CrossFit, P90X, Tae Bo, Pilates, Yoga, or any other program created for the purpose of making money, should be seriously questioned when considering the training of athletes for any specific sport or at any level of athletics.

ANYONE Can Do Our Job

I have long believed that sports coaches are not qualified or competent enough to satisfy the level of knowledge and experience that is required to plan and implement a strength and conditioning program. From the observation of multiple sports coaches trying to assert themselves as the strength coach, my beliefs stand firm. Sports coaches are NOT qualified to fulfill the role of a strength and conditioning coach and should NOT be permitted to do so by the NCAA or the institutions for which they represent.

Let’s be clear on this: the fact that collegiate strength and conditioning is very young means that it is evolving at a rapid rate. In early years, it was common for any coach that was familiar with the weight room to run the strength program, and some schools had the coach of each sport handle their own strength and conditioning. But what was necessary in the 1970s was becoming obsolete in the ‘90s. From a coaching qualification standpoint, what many schools were practicing in the ‘90s should be unacceptable by today’s terms. It is 2019. It is essential for the protection of our athletes that we demand a higher level of qualification from our coaches.

Sports coaches lack the scientific knowledge and education to adequately prepare a strength and conditioning program. They lack the practical knowledge and experience to properly and safely implement a strength program. They lack the technical knowledge to properly evaluate and coach technique for many exercises. And they lack the desire and understanding of the importance to remain focused and attentive for the entire workout rather than just paying attention to the bigger exercises.

From a review of sports coach job postings from all three NCAA divisions, it is clear that the educational and certification standards of sports coaches, to say the least, are very low. The most common qualification requirement is playing experience in a particular sport. Educational requirements are typically education beyond high school but rarely is there a requirement for the education to be related in any way to sports, exercise science, kinesiology, or any other related fields.

Some schools require a CPR or First Aid certification. Other than track and field and swimming, it does not seem that any sport has a certification demonstrating the qualification of coaches (but I could be wrong, as I have not performed a review of all sports). If there is a certification, it is certainly not a requirement by universities to hold a coaching position. Unfortunately, besides CPR, the only license or certification sports coaches are expected to have is a driver’s license.

The lack of educational and certification requirements for sports coaches shows why we, as strength and conditioning coaches, are not valued. If anyone who has ever played golf competitively is qualified to be a golf coach, then certainly anyone that has ever performed strength training in preparation for their sport is qualified to conduct strength and conditioning workouts. It’s JUST lifting weights and JUST running, so anyone can do it.

LISTEN: Table Talk Podcast Clip — The ONLY Way to Build Confidence

That is the mentality that we are battling, and it is coming from sports coaches and administrators alike. Why is it that we expect so little education from our sports coaches, but yet we give them so much power in regards to decisions that should be made by the strength coach, who is required to hold a related degree (sometimes a graduate degree), a certification, and to maintain continuing education for that certification? The strength coach is required to hold a higher level of education and certification but is then dictated to by a sports coach who holds no certification or related education. In what world does this make sense?

Ultimately, the sports coach is responsible for their team, so they must be comfortable with the program their team is following. Remember, it is the sports coach whose job is on the line if the team loses. While we can blame personal bias and lack of education for their gravitation toward irrational means of training, the problem is compounded by the strength coaches who allow sports coaches to dictate what they include in their program. Unfortunately, it is not always that the strength coach allows this to happen, but more so that their hand has been forced, and they have no power to decline the sports coach’s desires.

Furthermore, our own strength coaches do a disservice by utilizing extreme, unnecessary means with teams that do not share the same mindset as the typical meathead. Being a meathead when we are performing our own personal workouts is acceptable, but we cannot afford to be meatheads in our roles as strength and conditioning professionals. This damages our reputation with sports coaches and administrators, leading to a loss of respect and unwillingness to buy into what we are trying to accomplish.

While more educated than the typical sports coach, athletic trainers are also not qualified to be strength and conditioning coaches. An athletic trainer’s education is not equivalent to that of a strength coach. Nor is it better or worse. Many young athletic trainers feel that because they had one or two classes that covered topics related to strength and conditioning, they know everything there is to know about what we do. Their arrogance in this regard is appalling.

I cannot count the number of times I have heard young athletic trainers make claims in regard to strength and conditioning that come from very limited viewpoints and in some cases, are just wrong. However, for some reason, they feel they have the authority to tell strength coaches how we should be doing our job, and I have even seen some utilize their “unchallengeable authority” granted to them by the NCAA to demand that we, as strength coaches, perform our jobs within the scope of their limited viewpoint.

The ATC certification, which is a solid and highly regarded certification, is meant to certify them as qualified athletic trainers, not strength and conditioning coaches. While we should work closely with athletic trainers, and there is an overlap of our jobs when it comes to athletes recovering from injury, the roles of an athletic trainer and strength coach are different and should be looked upon as such.

Strength and Conditioning Coach of the Year? Who?

Is this really an award? Why do we feel the need to seek equivalency to sports coaches? Yes, every year, every conference and also the NCAA award the Coach of the Year to a coach from each sport. The NCAA does not offer this award to the best strength coach, however. Nor should they offer us an award.

It is fairly easy to identify a basketball coach who just had an undefeated season or a football coach who took his team from No. 2 to No. 10 to a top-10 team in just one season. The successes of sports coaches can be measured or made obvious by what their team has accomplished. However, how do you measure the success of a strength coach?

MEASURING STRENGTH BY SPEED: How Strong is Strong Enough?

There is no meaningful, objective measurement of the success of a strength and conditioning coach or program. We cannot compare testing numbers due to the inconsistency of testing procedures between schools. We cannot compare injuries because of the unfairness and lack of ability to identify the exact cause of each injury. We cannot utilize wins and losses because we know that some strength coaches do not utilize sound programming, yet their teams still win. We cannot compare coaching ability because most coaches are not visible enough to be accurately compared nor is there an objective way of evaluating the ability to coach.

Furthermore, there are probably more than 500 head strength coaches at the collegiate level (counting all divisions), so how do we truly evaluate and determine one winner when it is impossible to effectively evaluate the number of coaches?

But we have gone out on our own and created our own awards to give to strength coaches. Unfortunately, it is impossible to measure who is the best strength coach because of the reasons mentioned above. This is not to mention that the majority of non-football strength coaches are not well known beyond their own personal network. Division IAA, II, and III strength coaches are virtually unheard of. And who evaluates which coaches are good? There is no fair way of evaluating which coaches are the best coaches since it cannot be measured and coaches cannot be compared on a level playing field.

Beyond the considerations of how to evaluate strength coaches is determining who evaluates which coaches are good. We want this to be a decision voted on by our peers. While I am at my school working for the good of the athletes here, you are at your school doing the same. We cannot see each other coach. For all you know, I may step out of my office, write a workout on the dry erase board, tell the athletes to get it done and walk back into my office. Without having an evaluation system, we cannot actually know how good of a job each coach is doing.

Establishing a checklist or point system of organization contributions does not evaluate the quality of a COACH. What does hosting a podcast have to do with coaching? What does hosting a clinic have to do with getting athletes stronger? What does attending a clinic have to do with helping an athlete change directions more efficiently? What does teaching a class have to do with teaching an athlete how to do a clean or a squat properly? How does editing a book contribute to the athlete’s success? How did being a committee chair help a team stay injury free? An award for a strength and conditioning coach should evaluate how effective a coach is at coaching, not extra-curricular activities.

On top of all of this, the situation is made worse when the organization giving the award sets prerequisites for the award, such as paying to be members of frivolous registries or paying for additional certifications to say that you are elite. If a coach has earned recognition, then he or she should be recognized without having to pay for it.

For these reasons, we should eliminate all Strength Coach of the Year awards. These awards are no more than a popularity contest and accomplish no more than the creation of a facade to make other coaches (strength coaches and sports coaches alike) believe we are better and more important than what we really are. They are simply an ego booster.

The NCAA Certification Requirement: A Certified Debacle

We have failed to establish a credible certification that actually carries weight with the NCAA. For much of my career, I have lived by the belief that it is much more important to have a true knowledge of strength and conditioning along with the ability to coach rather to simply hold a piece of paper that says you are qualified to coach. However, it is quite apparent, in today’s world, that a certification is not only necessary but that it should be mandatory for anyone working in collegiate strength and conditioning.

GETTING YOUR FOOT IN THE DOOR: Grad Assistants: Read This Before Applying Anywhere

In 2014, the NCAA (Division I) passed legislation requiring strength and conditioning coaches to hold a nationally accredited strength and conditioning certification. However, what was initially expected is not how things ended up. Instead of requiring certification from either the NSCA or the CSCCa, the NCAA allowed any nationally accredited certification to be acceptable. Furthermore, there is no requirement of the coaches to provide any evidence of actually holding the certification. So, we are required to hold a certification, whether or not it is relevant to the practice of strength and conditioning at the collegiate level, and we are not held accountable as to whether that certification has actually been obtained or upheld.

We have a plethora of certifications in the fitness/strength and conditioning industry, but how many of them are actually valid for what we do at the collegiate level? The NCAA has made it clear that it does not matter which certification we hold — as long as it is nationally accredited. This means that we can have no prior experience in strength and conditioning, no related formal education, but we can take a weekend certification course and we will be qualified to be a strength and conditioning coach at the collegiate level.

This fact has diminished our profession to a level of unimportance, essentially stating that anyone can do it, regardless of their background, sending a message to university administrators and sports coaches that the knowledge necessary to be a strength and conditioning coach is minimal, subsequently meaning the educational background of a strength coach is of little value. After all, anyone can do it because it’s JUST lifting weights.

The decision by the NCAA to require certifications has led many strength coaches to turn to the U.S. Track and Field and Cross Country Coaches Association to take advantage of a certification designed specifically for strength training for track and field athletes. This certification offers an easy solution to the uncertified coach. The USTFCCA strength and conditioning certification is centered on only one sport. There are no educational prerequisites to take the course or hold the certification. In order to obtain an advanced endorsement to the certification, a degree is required, but there is no requirement that the degree is related in any way to strength and conditioning or sports science.

The creation of the track and field strength certification has allowed uncertified and uneducated strength coaches an easy route to obtain a certification that allows them to bypass the need for a real, strength and conditioning certification. An argument can be made that this certification is relevant for track coaches or strength coaches who work directly with track and field athletes; however, many coaches who have no interest or involvement in track and field are obtaining this certification because it is the easiest route to satisfying NCAA requirements.

Challenges at the Lower Levels

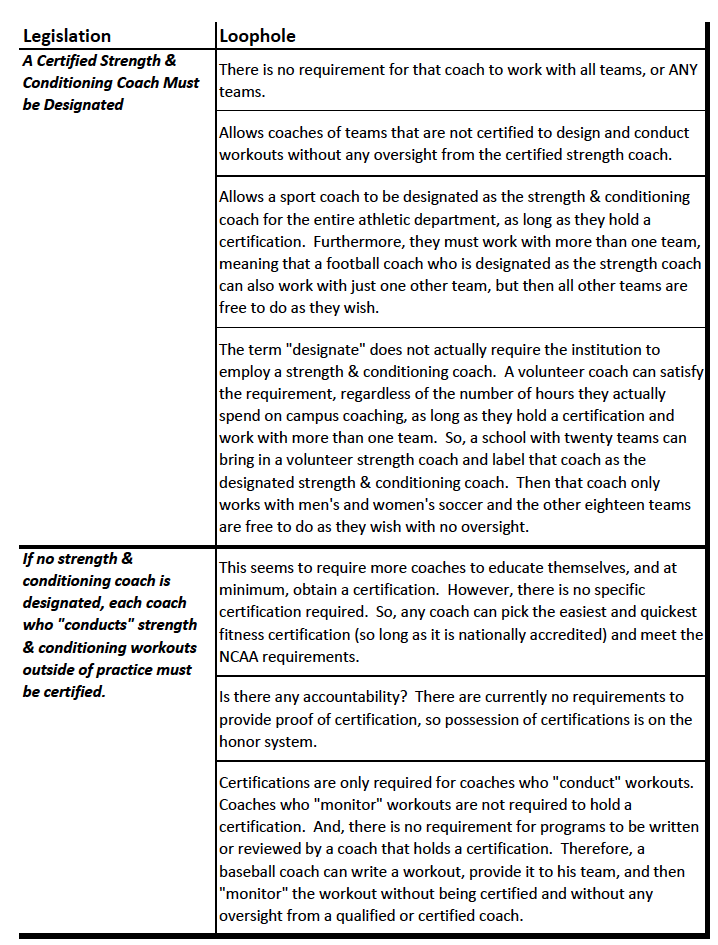

In 2015, in the NCAA Division II, there was proposed legislation requiring strength and conditioning certifications, which passed in 2016. At first glance, this legislation can be viewed as a success because many Division II institutions hired their first-ever strength coaches between the years of 2014 and 2017. However, there were so many loopholes in this legislation, it should be questioned as to what good this legislation has actually done.

In Division II, a school is required to designate a certified a strength and conditioning coach, and if they do not, any coach that “conducts” strength and conditioning workouts outside of practice must obtain a strength and conditioning certification. Below is the Division II legislation and the loopholes schools can use to get around it when they are not willing to fund a strength and conditioning department or coach.

Money Trumps All

If a school cannot afford to provide the proper staffing in order to provide adequate care for their student-athletes, maybe they should re-think the idea of carrying so many teams. Unfortunately, many schools only keep teams around to drive enrollment. They do not utilize athletics for the benefit of the student-athletes but instead to bring in money for the school. This is especially apparent at lower levels when you see enforced, enlarged rosters with small scholarships just to obtain increased enrollment.

As a generic and simple example, I am going to use a tuition and fees estimate for each student-athlete of $30,000. If a school provides a $1,000 scholarship for each athlete to entice them to enroll, there is $29,000 of revenue generated for each student-athlete. So, increasing the roster from 25 to 50 athletes means an additional $725,000 for the school. When this is done for multiple teams or new teams are created even more revenue can be generated. Unfortunately, schools do this while employing only one soccer coach for the team, one or no strength coaches for the entire athletic department, and small athletic training staffs. Essentially, schools are saying, “Screw the athletes, we want money.” (I’m sure someone in the business office can explain how and why this example is so inaccurate, but I’m also sure anyone with a shred of common sense can understand the point I’m trying to get across.)

The end result is bad for everyone. Teams are not competitive and it’s teaching athletes that winning is not important as long as they participate. Sports coaches are forced to maintain large rosters of athletes that don’t really care about winning. Sports coaches see the writing on the wall and do not put out the effort necessary to win. Injuries are prevalent. Strength coaches and athletic trainers are overworked. For those coaches and athletic trainers in these situations who are not overworked, they are most likely cutting corners, again, providing less than adequate care and placing the athletes at greater risk.

Til Death Do Us Part…

In the summer of 2017, Bob Bowlsby (commissioner of the Big 12) announced that the NCAA will be examining how strength and conditioning coaches are considered qualified to do their job. Referring to both the NSCA and CSCCa, he stated, “Neither of them have tremendously strong certification processes” (Barnett).

Whether true or not, this is our perceived reality. This is the reality that we have created for ourselves.

He went on to state, “…the deaths are happening during conditioning and off-season practice. Very few of them are happening during the season, during contact, during regular preparation.”

It is common knowledge that January and June produce the most newsworthy stories of rhabdomyolysis, sickle cell anemia, hospitalizations, and deaths. While this occurs in many sports, I will make my references to football. In January, the upcoming season is eight months away. But too many coaches feel it is necessary to implement workouts that would be difficult for athletes that had already been training for several months. The result is that athletes who recently finished a season went home over the break and did nothing but sit around for six weeks and are exposed to workouts for which they are not even close to being physically prepared.

SUMMER BREAK OUTLINE: 8-Weeks-Til-Camp Summer Program for High School Football

Why do we do this? Have we never read a book? I cannot count the number of times I have read about how we need to take time to prepare the athletes for the demands of upcoming training. I am probably guilty of this to a point, but I also understand the importance of working with what we currently have and not what we should have in six months.

Many years ago, as a young strength coach, I had an in-season team come back after the semester break in poor condition. I remember being upset with the athletes and the sports coach impressing upon me that, while they didn’t do their part, that is what we had to work with. In essence: trying to train them hard to prove a point would be no better than slamming our heads against a brick wall. It wouldn’t help and would likely make things worse.

Another example of a team I once worked with is when I had a coach of a fall sport try to convince me I should have his team run 26 110s on the first day back in January after the semester break. He told me how a former strength coach would do this and how the girls would be crying because it was so hard. There was no point to this workout. Their season started in August. He could not give me one good reason to implement this workout. The only justification he could give is that it was hard, repeatedly emphasizing how many of the girls were crying. I refused to do this, and it did not work out well for me. In many cases, this is a perfect example of how our own strength coaches are putting us in a bad situation by succumbing to the ill-informed demands of uneducated sports coaches.

I recently had a discussion with a strength coach who often consults with me about the conditioning for one of his fall teams (soccer). The coach had been pushing him all January and February to make the conditioning harder despite his resistance. In mid-February, he reluctantly had the team run 24 80-yard sprints (1.1 miles). After the workout, the coach told him he wasn’t having the team run enough and that for them, a mile is only a warm-up. This was the last conditioning session that the strength coach was allowed to conduct with the team. The soccer coach took over conditioning from that point forward.

It is this type of practice that is earning our profession a bad name. Practices of this nature are telling administrators that strength coaches have no apparent value and that any sports coach is just as qualified to do our job. Certainly, sports coaches can hospitalize and kill athletes just as well as we can!

As strength coaches, we are shooting ourselves in the foot by implementing stupid practices just because the sports coach wants us to implement a workout for which their athletes are not prepared. It is their team, but we are supposed to be the coaches who are knowledgeable enough to know what we should and shouldn’t be doing. Many sports coaches have no knowledge of physiology and just want to see their athletes go hard.

In March 2017, CBS Sports published an article titled, “The Unregulated World of Strength Coaches and College Football’s Killing Season,” by Jon Solomon and Dennis Dodd. The title alone insinuates how we are failing to gain respect from anyone. The content of the article discusses the current perception that we have created for ourselves. We have not established credible certifications that garner respect from those that we need to support us. We have created a perception that we implement workouts that are designed to torture athletes and result in visits to hospitals and funeral parlors.

LISTEN TO THE ATHLETES: Through the Players' Eyes

We need to wake up! We need to quit being stupid! We need to quit trying to prove a point. We need to quit trying to show sports coaches how hard we can make workouts by making athletes puke, cry, or pass out. We need to start caring for the athletes we are supposed to be trying to help. We need to start utilizing the knowledge that we have and the information that is available to us. We need to start being professionals!

The items listed above show why we need to have a credible and mandatory certification along with the authority to make and enforce decisions in regards to safe practices in strength and conditioning. We need an “unchallengeable authority” similar to that of athletic trainers. We need to be able to refuse to do stupid practices and instead implement logical progression to obtain the results that everyone desires without the fear of being removed from teams, or in the cases of football and basketball, being fired.

Quit Telling Me You Have Your CSCS

At the point we are at, the CSCS may no longer be a viable certification for strength and conditioning coaches at the collegiate level. In order to be a qualified strength and conditioning coach, a coach needs to be both knowledgeable and able to effectively coach in a team setting. Simply having a base level of knowledge does not qualify a coach as capable.

Too many non-strength coaches are beginning to get their CSCS so they can have a strength and conditioning certification, but they have no real comprehension of what it takes to be a strength coach. A related degree is not required to obtain the CSCS, meaning anyone can take the exam and acquire a certification regardless of the nature of their education, so long as they have received a bachelor’s in any degree.

Sports coaches and athletic trainers simply get the certification so they can say they are qualified. They then proceed to tell strength and conditioning coaches how to do their job with no real knowledge of the field, other than what they acquired to pass the test. From a knowledge standpoint alone, the amount of knowledge required in this field is far more vast than any certification can actually measure. Much of the knowledge used by experienced strength coaches was acquired through self-education that occurred after taking and passing the certification exam. Therefore, how can a certification that can be so easily obtained by those only willing to put in the minimum effort to obtain knowledge be an acceptable means of determining the qualification of a coach?

I all too often hear sports coaches and athletic trainers introduce themselves to me, followed by the line, “I have my CSCS.” I then observe these “certified” individuals take teams and athletes through workouts while violating what should be standard practices of any strength coach. I have actually observed these individuals sit (and even lie down) on unused equipment or meander through the weight room with a disinterested demeanor while never uttering a word to their team. While they sip their morning coffee, their athletes go un-coached, use whatever weight they feel like using, and show up and leave whenever they feel like it. I hope the coffee was good because your team’s workout was horrible!

READ MORE: A Fair Assessment of the CSCCa and NSCA

Once the gold standard for strength and conditioning certifications, the ease of acquiring the CSCS has rendered it obsolete in today’s world of collegiate strength and conditioning. Too many uninterested individuals are obtaining the certification so they can do their own thing unchecked. Too many individuals are getting certified to merely say they have a certification. They want to feel important. They want to impress others. They want to be elite. They want to be elite without ever doing the work to accomplish anything.

Quit telling me you have your CSCS! You’re still not a strength coach. You still don’t know what it takes to do this job. Doing just enough to pass a test does not mean you are knowledgeable about this field. The letters behind your name supposedly say you are qualified to have the job, not that you are necessarily qualified to do the job.

A certification merely states that the minimum knowledge level of the subject to be certified in has been obtained. A certification tested by written means does not indicate the ability to apply that knowledge in a practical setting. Being knowledgeable and being able to apply knowledge in a practical setting are two very different things.

As a strength coach, having both qualities is of utmost importance. With that said, it cannot be understated that the possession of knowledge is meaningless without the ability to apply that knowledge in a real-world setting. However, the ability to coach can still be beneficial and productive even with a minimum level of knowledge.

You’re What? Those Letters Cost How Much?

We have an obsession with placing as many letters behind our name as possible. I have no respect for letters, and trust me, that’s not going to change. I have respect for coaches who have been in the trenches coaching. I respect coaches who have been in the game for a long time. I respect coaches who back up what they say with what they do. I respect coaches who genuinely care about the athletes they are trying to help.

Paying money to put a series of four or five letters behind your name, to get your name on a list, to be eligible for an award, or to be eligible for additional benefits is no more than a hoax being sold by an organization trying to build revenue. Additional certifications and registries are a facade. To the uninformed, it makes the coach appear more knowledgeable, experienced, or just better, but in reality, none of those things are necessarily true.

There are so many coaches in the collegiate ranks working to help athletes who do not have the time to seek out additional certifications or the desire to pay to get their name on a list who do not get recognized... ever.

Conclusion

Collegiate strength and conditioning is still a young profession, meaning that it is growing and evolving rapidly. What comes with that is that most people have no comprehension of the knowledge that we have or the demands of our job. One thing that needs to be recognized is that we are required to have a certification to be a strength coach at the collegiate level. But every coach and administrator, who doesn't even have related education, much less a certification, think they know more than us and can tell us how to do our job. Has anyone ever stopped and asked why we are required to hold a certification?

Unfortunately, the NCAA is not requiring universities at all levels to hire certified strength coaches, which exacerbates the problem. Some schools are getting their sports coaches to acquire a certification, but the problem is they only studied enough to pass a test and still do not have the knowledge or experience to do the job in an appropriate manner. Allowing this to happen is doing a disservice to the athletes and teams we should be trying to help.

References and Recommended Reading

- Allen, David. (Apr. 30, 2018). Three Things I Would Change About the Fitness Industry.

- Barnett, Zach. (July 17, 2017). NCAA to Examine Strength Coaches’ Certification, Oversight Process.

- Burnsed, Brian. (June 26, 2015). Competitive Safeguards Finalizes Division II Strength and Conditioning Coach Proposal.

- Burnsed, Brian. (Summer 2018). The Breaking Point.

- Coach G. (Sept. 7, 2017). We Better Get It Right – Securing the Future of S&C Before It’s Too Late.

- Dodd, Dennis. (Jan. 17, 2017). College Football’s Unchecked Conditioning Culture is Dangerous for Players.

- Dodd, Dennis. (Aug. 14, 2017). Kent State Fires Strength Coach in Charge During Death for Falsifying Certification.

- Frey, Jeremy. (July 18, 2018). So You Want to Be A Collegiate Strength Coach: Untold Truths of the Job.

- Solomon, J. & Dodd, D. (March 10, 2017). The Unregulated World of Strength Coaches and College Football’s Killing Season.

- Watts, Mark. (Oct. 10, 2016). The Evaluation of a Strength and Conditioning Coach: A Process-Based Profession in an Outcome-Based System.

- (Dec. 3, 2015). 2016 NCAA Convention Division II Legislative Proposals Question and Answer Guide.

David Adamson was the strength and conditioning coach for the Missouri University of Science and Technology from 2016 to 2018 and now serves as a consultant for collegiate strength coaches. Prior to Missouri S&T, he spent nine years as the assistant director of speed, strength, and conditioning for the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP). He was involved in coaching at the university level from 2001 to 2018, including stops at Virginia Commonwealth University and Arizona State University. In addition to coaching, David is a student of strength who lives by his experience under the bar. He began lifting in 1993 and competed in powerlifting from 2001 to 2016. During this time, he competed in many different gear divisions, including raw, and in every weight class from 181 to 242.

Why would we want to get rid of both our governing bodies? The NSCA and CSCCa have done an excellent job in promoting the profession and providing a venue for coaches to meet, exchange ideas, learn, etc. I am promoting other ideas which are discussed in the fourth article.

The SCCC is a good model to work from. Again, I discuss this in the fourth article. I never took the SCCC exam, so do not know exactly everything that goes into it. I really like the idea of a mandatory internship and the idea of having to sit with a Master strength coach to answer questions about a program written by the testee. I think these are great ideas that strengthen the quality of a certification. However, we cannot have two certifications, as we do currently.

You can only serve one master.

Yes, I agree there are aspects of S&C that athletic trainers use to further the rehab process just as there are aspects of athletic training/physical therapy that many strength coaches use. I don't see any problem with that as long as we are working in our own realm.

The problems I was referring to were athletic trainers overriding the strength coaches by telling the athletes that they needed to perform exercises within the S&C workouts utilizing a different technique than what the strength coach had taught them. Another example is when I saw an athletic trainer cancel lifting sessions and even a sport practice because they did not feel the team had recovered enough based off a subjective pencil & paper test. These examples are outside the scope of athletic training and abuse of the "unchallengeable authority" that has been granted to them by the NCAA.

I am fully aware that not all ATs are like what I described. In fact, I have worked with many excellent ATs who I have had great relationships with. The examples I gave were ATs who were young, inexperienced, egotistical, and not held accountable in any way.

The point I had tried to make in a separate post was that ATs should not be in charge of S&C, but that we should fall under the same umbrella with one individual as an associate AD being in a supervisory position over both departments. Furthermore, ATs and S&C coaches should not have to fear losing their jobs due to sport coaches not having a proper comprehension of what we do or to being unhappy about basic personality differences.