Introduction: Being Right Here

This is the final chapter of the “Motivation” project (see below). We now know how people set themselves (or are set) in motion, or how they get motivated. We explored how they can develop extreme emotional attitudes (passion), commitment and adherence to a goal. I pointed out that for all these things there are always going to be two ends of an autonomy spectrum in which at least one end is an ideal type (it doesn’t exist in reality). At one end of the spectrum, we have the completely autonomous individual that has absolute power and control to establish all his goals and strategies (that is the ideal type); at the other, the completely disempowered individual (not an ideal type: there are too many examples among severe illness victims and victims of negative social/environmental conditions).

If we consider just the autonomy/power/self-regulated side of the spectrum, it is possible to identify what the individual seeks to achieve and even what their top, transcendent goals (missions) are. But what do they really want?

They want a “good life”. They want to experience the highest possible match between the track or the achieved goal and an ideal state inside their minds. Happiness, well-being, fulfillment, peace, pleasure – they all fit into this state of balance and harmony between “being there” and the abstract, subjective ideal state.

At the core of extreme well-being is a state of consciousness and physical experience that has been called flow.

RECENT: Goals and Performance: Concepts and Application

A few times people have asked me what was there, under the bar, that kept me going back, and makes me keep going, and going. These are some of the answers I managed to provide. I also told them that words couldn't precisely capture that state:

“Under the bar, there is absolute freedom. I may or may not experience it. It is rare but when it happens, I find myself in a timeless, spaceless, boundless and especially ego-less condition as if I don’t even exist, as if I am nothing, as if I am everything, or as if I am movement itself. It’s eternal… but then it’s over. It is so good, it feels so perfect, so right, right where or what I’m supposed to be, that it’s worth living and dying for. It didn’t happen too many times in that intensity. Call it transcendence or bliss.”

I learned not to add “it’s a bit like the opposite of death: instead of merging into nothingness, it is merging into allness" because usually, the response is "you lost me there". Considering that for a few years all the media wanted to know from me was related to suicide, an inevitable aura of religiousness followed any conversation.

I have known martial arts masters as well as yogis who, after hearing this description, diagnosed them according to their system as the result of deep mindfulness practice. What term they offered to define it is unimportant. What they all agreed on is that is an altered state of consciousness in which one feels almost completely “there”, present, in an intense focus and with the exclusion of “everything else” (all worries, all past and all future).

What is Flow?

The concept of flow was developed by Mihály Csíkszentmihályi (1975) and describes a psychological state of optimal attention and engagement. Csikszentmihalyi was then concerned with autotelic (autotelic means something done for the sake of it or something self-rewarding) activities with strong achievement content, such as chess, rock climbing, and surgery. It has been simply defined as “a good life”: "a good life is one that is characterized by complete absorption in what one does" (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014).

You may have come across the same concept under a different terminology such as “being in the zone” (Seham 2001, Copper 1998). This term has been dropped by the scientific community and flow is the preferred choice.

The following are scholarly definitions of flow:

“(…) a deeply rewarding and optimal experience characterized by intense focus on a specific activity to the point of becoming totally absorbed in it, and the exclusion of all other thoughts and emotions. Flow experiences tend to be harmonious for the individual and involve a sense of everything coming together, or clicking into place, even in challenging situations. As such, the person is often left feeling that something special has just occurred and these experiences can be highly valued and positive” (Csikszentmihalyi 1997)

"Flow is a very positive psychological state that typically occurs when a person perceives a balance between the challenges associated with a situation and his or her capabilities to accomplish or meet these demands" (Csikszentmihalyi 1997)

"These (flow) characteristics or dimensions of flow (...) include (...): challenge-skill balance, merging of action and awareness, clear goals, unambiguous feedback, concentration on task at hand, sense of control, loss of self-consciousness, time transformation, and an autotelic experience" (Jackson et al 1998)

"Experiencing frequent flow states within a specific activity leads to a desire to perform that activity for its own sake; that is, the activity becomes autotelic” (Csikszentmihalyi 1975, 1997)

Now compare with these:

“… transcendental consciousness, the perfect state of being, of self-realization, of freedom and of "realizing the whole universe as the Self" (Deutsche 2013 on the concept of moksha).

"(…) a transformed state of personality characterized by peace, deep spiritual joy, compassion, and a refined and subtle awareness. Negative mental states and emotions such as doubt, worry, anxiety, and fear are absent from the enlightened mind." (Keown 2000 on the concept of nirvana)

"Someone who has attained [...] the state of nirvana (…) sees things (as) non-dualistic and therefore non-conceptual. [...] We see clearly, and nothing seems imposing, since nothing is imposed from our part. When there is nothing we do not like, there is nothing to fear. Being free from fear, we are peaceful. (…) In this way there is no burden. We can have inner peace, strength, and clarity, almost independent from circumstances and situations. This is complete freedom of mind without any circumstantial entanglement; the state is called "nirvana" [...]. (Tulku 2005 on the concept of nirvana)

The similarities are undeniable. Were ancient mystics into something? Were they describing the same phenomenon? We don’t know. Nietzsche ’s philosophy of will, his ideas of free will and will to power have commonalities with Buddhist practice and thought, including nonattachment, nihilism, no-self, and meditation, all of which bear some resemblance to our modern concept of flow (Hanson 2008).

Since the beginning of flow research, the following characteristics have been associated with the experience. Taken together, they describe what is known as the “autotelic experience” (Csikszentmihalyi 1975).

- Concentration on the task at hand (i.e., complete focus with no extraneous or distracting thoughts);

- Action-awareness merging (i.e., total absorption, or feeling at one with the activity);

- Loss of self-consciousness (i.e., decreased awareness of self and social evaluation)

- A sense of control over the performance or outcome of the activity

- Transformation of time (i.e., the perception of time either speeding up or slowing down)

Scientists have become interested in flow since the early 1990s because they wanted to understand intrinsic motivation and autotelic activity. Apparently, both were associated with success in certain fields (Jackson & Roberts 1992). The interest of flow research in sports is the intersection of peak experience and peak performance. What the body of research has shown is that these experiences are rare, elusive and unpredictable (Swan et al 2012).

Although there is a lot of empirical research on flow, there is a consensus that much more is needed. The survey and interview studies have methodological problems, such as questions that lead the respondent and skew the results.

How Does Flow Happen?

Although there is still a lot to learn about flow, there is evidence suggesting that certain combinations of circumstance and personal characteristics favor the experience of flow.

Jackson and Roberts (1992) examined the role of goal orientations and perceived ability as psychological correlates of flow states. The following variables are positively correlated with the occurrence of flow:

- Endorsement of task involvement

- High perceived ability

- Frequency of flow experience

Swan and collaborators (2012) listed the following as prerequisites for flow to take place:

- Challenge-skill balance

- Clear goals

- Unambiguous feedback

Certain personal characteristics seem determinant of whether flow may or may not take place:

- The "autotelic personality" (Csikszentmihalyi 1997, Jackson et al 1998): some people are better psychologically equipped to experience flow or experience it more frequently.

- The "non-self-conscious" individual (Logan 1988): the individual who is able to become engrossed in an activity because of the lack of preoccupation with the self.

- The "autonomous individual": work in the area of intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan 1985) suggests that those who feel more in control of their own actions are more likely to be intrinsically motivated. They observed a relationship between flow and intrinsic motivation.

- The "interactionist framework": certain dispositional and state psychological factors interact with sport context factors and determine whether or not an athlete is likely to experience flow (Kimiecik and Stein 1992)

Jackson and Roberts (1992) studied the relationship between types of goal orientation and the experience of flow. There are two types of goal-orientation according to the authors:

- Task goal-orientation: individuals who strive for learning and improvement (self-referenced ability conceptions)

- Ego goal-orientation: individuals who emphasize winning, outperforming others and demonstrating ability (normative ability comparisons)

They found a correlation between task orientation and flow in college athletes. Later, Jackson and Marsh developed the Trait Flow Scale (Jackson & Marsh 1996). It is difficult to totally immerse oneself in an activity when worry or tension is the primary focus. Competition anxiety, thus, is not conducive to flow (Jackson et al. 1998)

The identification of inherent traits or personality characteristics that consistently show to be conducive to the flow experience raise questions concerning the interplay of nature and nurture. Certain social settings (family and cultural) are stimulating while others are inhibitory of those traits. What about physiological traits? Ulrich and collaborators (2014) studied 27 human subjects using functional magnetic resonance perfusion imaging. They concluded that neural activity changes in certain brain regions reflect psychological processes that map on the characteristic features of flow: coding of increased outcome probability (putamen), deeper sense of cognitive control (left anterior inferior frontal gyrus), decreased self-referential processing (medial prefrontal cortex), and decreased negative arousal (amygdala).

At least one study also showed that there is a U-shaped distribution in cortisol release associated with flow experience in team sports (Sabzaligo & Nojavan 2017). Flow is experienced at a certain level of arousal and that distribution makes sense: too little or too much arousal are not conducive to flow.

The flow experience is not restricted to elite sport. In fact, it was scientifically conceptualized to explain a range of other activities. If we consider that mystics have been describing something similar concerning meditative practices, flow may be more pervasive (but also rarer) than we think (Chilton 2013, Csikszentmihalyi 1996).

The Takeaway

One of the first concepts I introduced about motivation was of “meaningful activity”. We have now come full circle to the experience of meaningfulness. The experience of flow is at the heart of meaning. Meaning of everything: of one’s activity, of oneself and of one’s life. As flow is a result of a combination of factors (again, nature and nurture), the pursuit of meaning is optional.

Being intrinsically motivated is not superior to being extrinsically motivated; being task-oriented is not superior to being ego-oriented. Achieving goals does not confer superiority over those not achieving goals. In fact, the vast majority of people will have no clue about what an experience of “total engagement”, “freedom from worries” and “loss of self-awareness” even means.

Another takeaway is what has been called by researchers emergent motivation: although the entire goal structure may not change, proximal goals may arise out of the flow interaction, making the whole goal-oriented life a fluid, dynamic, self-regulating, permanently self-constructing and self-perfecting system (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014).

As the saying goes, anything worth doing is worth doing well. Maybe, just maybe, anything worth doing well is worth being fully immersed in. If for anything else, the “optimal feeling” is associated with well-being and happiness.

Is this for everybody? Is this for every athlete? Of course not. Let’s face it: the majority of athletes are predominantly extrinsically motivated and ego-driven. Their deepest level of self-disclosure frequently reveals some personal damage that led to a sense of inferiority, only to be overcome by the relentless and obsessive striving to be better than everybody else, “the best”. This discourse doesn’t deviate that much from an avenging approach: “Now who’s the underdog?”. This person will never experience flow.

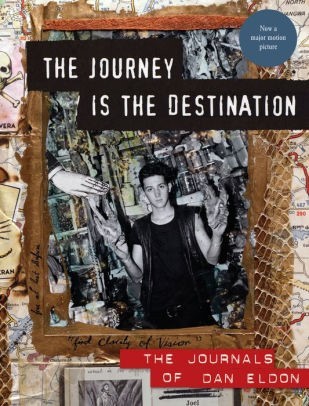

I’m sure most of the athletes reading this will identify themselves with the Muhammad Ali saying below and not with writer and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson or photojournalist, artist and activist Dan Eldon. Ali is the epitome of extrinsic motivation while the other two lean to the intrinsic motivated, task-oriented life.

What Ali is telling us from the grave is that it is worth doing everything and anything just to prove yourself the best: the GOAT (greatest of all time). What all the research on flow tells us is that, since the dawn of History, the wisest men have been willing to do everything and anything to transcend and reach plenitude, self-fulfillment, and peace.

Your choice, as always.

From Bamsey November 23, 2017 - https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/23/us/dan-eldon-journey-is-the-destination/index.html and Eldon (1997). Retrieved on February 2019.

References

- Bamsey, B. 'The Journey is the Destination' tells the incredible story of Dan Eldon – CNN, November 23, 2017 https://www.cnn.com/2017/11/23/us/dan-eldon-journey-is-the-destination/index.html (retrieved in 2019)

- Copper, A. "Playing in the zone: Exploring the spiritual dimensions of sport." (1998).

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row. (1997).

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, and Isabella Csikszentmihalyi. Beyond boredom and anxiety. Vol. 721. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1975.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. Vol. 56. New York: Harper Collins, 1996.

- Deci, E.L. & Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press, 1985.

- Deutsch, E. The self in Advaita Vedanta, in Indian philosophy: metaphysics, Roy Perrett (Editor), Volume 3, Taylor and Francis, pp 343-360, 2013.

- Eldon, Dan. The journey is the destination: The journals of Dan Eldon. Chronicle Books, 1997.

- Hanson, J. Searching for the Power–I: Nietzsche and Nirvana. Asian Philosophy: An International Journal of the Philosophical Traditions of the East. 18 (3): 231-244, 2008.

- Jackson, Susan A. "Toward a conceptual understanding of the flow experience in elite athletes." Research quarterly for exercise and sport 67, no. 1 (1996): 76-90.

- Jackson, Susan A., and Glyn C. Roberts. "Positive performance states of athletes: Toward a conceptual understanding of peak performance." The sport psychologist 6, no. 2 (1992): 156-171.

- Jackson, Susan A., and Herbert W. Marsh. "Development and validation of a scale to measure optimal experience: The Flow State Scale." Journal of sport and exercise psychology 18, no. 1 (1996): 17-35.

- Jackson, Susan A., Stephen K. Ford, Jay C. Kimiecik, and Herbert W. Marsh. "Psychological correlates of flow in sport." Journal of Sport and exercise Psychology 20, no. 4 (1998): 358-378.

- Keown, Damien (2000), Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction (Kindle ed.), Oxford University Press

- Kimiecik, J.C., & Stein, G.L. Examining flow experiences in sport contexts: Conceptual issues and methodological concerns. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 4: 144-160, 1992.

- Logan, R.D. Flow in solitary ordeals. In M. Csikszentmihalyi & I. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.). Optimal experience: Psychological studies of flow in consciousness (pp. 172-180). New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Nakamura, Jeanne, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. "The concept of flow." In Flow and the foundations of positive psychology, pp. 239-263. Springer, Dordrecht, 2014.

- Sabzaligo, H. & H. Nojavan. The Study of the Relationship between Flow and Cortisol Release under Stressful Situations. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention. Vol 6 (6):44-48, 2017.

- Seham, Amy E. Whose improv is it anyway? Beyond Second City. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2001.

- Swann, Christian, Richard J. Keegan, David Piggott, and Lee Crust. "A systematic review of the experience, occurrence, and controllability of flow states in elite sport." Psychology of sport and exercise 13, no. 6 (2012): 807-819.

- Tulku, Ringu (2005), Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism, Snow Lion

- Ulrich, Martin, Johannes Keller, Klaus Hoenig, Christiane Waller, and Georg Grön. "Neural correlates of experimentally induced flow experiences." Neuroimage 86 (2014): 194-202.

Many of the concepts referred to here are described in the articles below:

- Why Do You Lift — Meaning, Identity, Hope and Passion

- Why Do You Lift — Defining Passion

- Why Do You Lift — Defining Hope, Motivation, and Risk

- Why Do You Lift — What the Absence of Motivation Teaches Us (Suicide)

- The Role of Grit in Sport Performance

- The Role of Mental Toughness in Sport Performance

- The Role of Self-Regulation and Control in Sport Performance

- The Plan: Walking the Talk

- Goals and Performance: Concepts and Application