This is a video we made to address Margaret's difficulties in bracing her back against her belt and attempting to get away from just pushing her abdomen into the belt in an attempt to brace.

RECENT: Joe Sullivan Rants — Go to Therapy!

Powerlifters and strength athletes, in general, are continually cued to "push into their belt" or cued to have a "big belly," and both of these phrases use verbiage that tends to have the lifter focus on the front of their body.

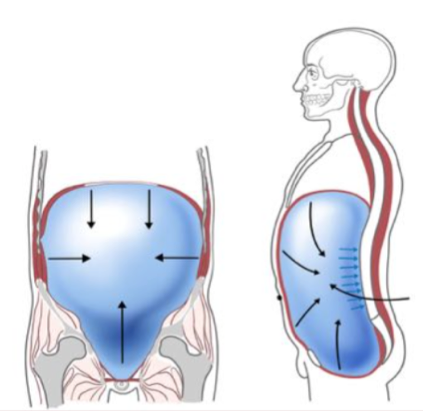

However, the diaphragm expands downward and operates under the assumption that the air drawn in by the athlete will cause the torso to expand in 360 degrees, not just out toward the front. This means that in order to brace in the best way possible, we need to rework our understanding of doing so in the first place.

When you inflate a balloon, what happens? One side does not inflate; the stretchy rubberized shell expands in EVERY direction. Our bodies are malleable and mobile shells, and we must allow the air to expand inside of us in every direction, and be proficient at using our abs (front), our obliques (sides), and our spinal erectors (backs) to brace under load in order to be able to produce as much force as possible, otherwise we are leaving opportunity open for mistake, and therefore, leaving pounds on the platform.

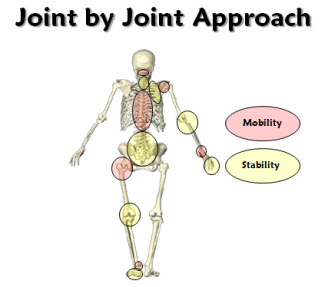

Now, air is not the sole thing that is used to brace. We have muscles that we use to stabilize the torso. The air is simply the added oomph to prevent us from breaking down and to prevent the athlete from passing out under heavy load. Each of the muscles I listed previously must be used with the others in an effort to make our torsos rigid and immobile, while our mobile joints, like hips and shoulders, allow the load we want to move and allows us to be able to do so.

WATCH: The Quadruped Row Exercise for Lat Isolation Issues

As a coach, it is up to you to develop an eye to see where an athlete may be deficient in these abilities, such as bracing their torso, and even after years and years of developing that skill, it is still very difficult. Sometimes it takes many training sessions and a large amount of trial and error before realizing where the break in the chain may be. Adding in other variables, such as biases toward certain ways of moving (i.e., relying on your arch to stabilize, wide stances to make up for lack of mobility, and large arches on bench) to cut ROM so that the demand to brace is lessened can make for a great deal of observation to be required. And then other times, you can say, "What in the fuck are you doing?" because it's so obvious.

This is a video of Janis Finkelman squatting a year ago. Note the break in her hips as she starts the descent. There is a lack of rigidity we were discussing above, and it is causing a leak in power. As a coach, you need to be able to tell it is due to her rushing the setup, rushing the walk out, and generally, rushing the entire movement.

Compare it to a much more patient and methodical approach to find the rigid spine FIRST, maintain it, and THEN begin to be mobile (start actually squatting) as demonstrated by her and Cailer Woolam below (two long-limbed lifters) along with myself.

As you can see from the videos above, there is a skill to being patient while executing despite having the weight of the world on your shoulders.

Drills such as crocodile breathing are useful and can easily be implemented into any warm-up, but as athletes and as coaches, we all need to remember it must be replicated under load. If we spent 30 minutes absolutely NAILING our warm-ups, but as soon as we get under 50 percent of our max and it looks like dog shit, what did we achieve?

READ MORE: Everything You Need to Know About The Max Effort Method

Be smart with your movement, but above all else, have common sense. If it looks bad, fix it; if it looks better, keep fixing it! And never stop improving.

As soon as you or your athletes become complacent, it is very easy to fault back into more relaxed movement patterns, and then you will find yourself in the same position leaking power and needing another coach’s eye to run diagnostics on where things are breaking down.

1 Comment