I know what you need.

Soak that up. Reading it might comfort you, or it might upset you, but either way: I do know what you need. I don't know the specifics of your circumstances, and you don't know mine (even if you think you do). I don't know the bills, or overhead, or fading love you are worried about. I don't know if your significant other has become unbearable. I don't know if you're able to access food or you're afraid of losing what shelter you've got.

What I do know is that you need the same thing as me.

You need something to fixate on, we all do. A goal that—even in your current, emotionally, financially or otherwise crippled state—you are capable of attaining or, at least, working toward. A goal is what we all need; something to aim at, something which is currently far away. And on our way toward it, we need goals or focal points; sharp and precise, crisp and clear. We need targets that will assure us we are on the right track when we hit them. More than that, we need to commit ourselves. If the thing we commit ourselves toward improves us, it's that much better.

I am doing what I know, but more than that, I am doing what I am able. I suggest you do the same.

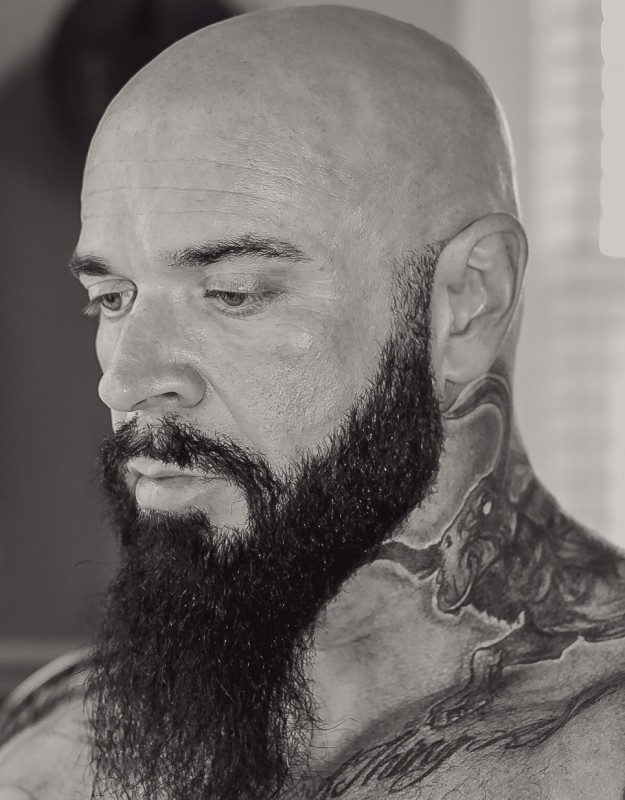

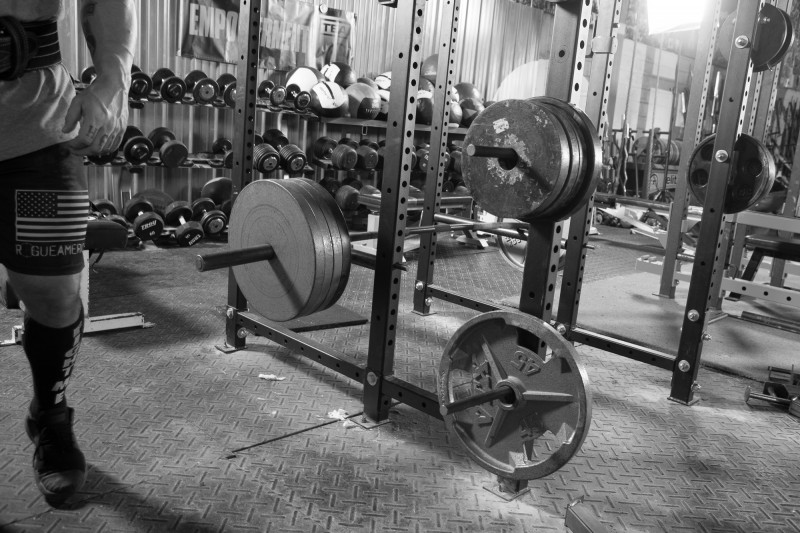

Keyhole Barbell is part of my home. It is located within the church, where I also live. With that said, the aggregate of all my current training, beyond activation work, is made up of SSB squats and bench presses. That's it. Anyone with a power rack, an SSB, a power bar, and a bench could easily execute a similar strategy if they had a reason to. I am not suggesting that.

You don't need bars or racks of any kind to set up a plan that will yield positive psychological dividends and help you keep moving through the troublesome situation in which most of us currently find ourselves.

Replace my nonsense with your nonsense. Replace my goals with your own unique goals; goals that fit the criteria I outlined above. As I explain my thinking with my focus, take the time to consider how this sort of thinking might help you with yours.

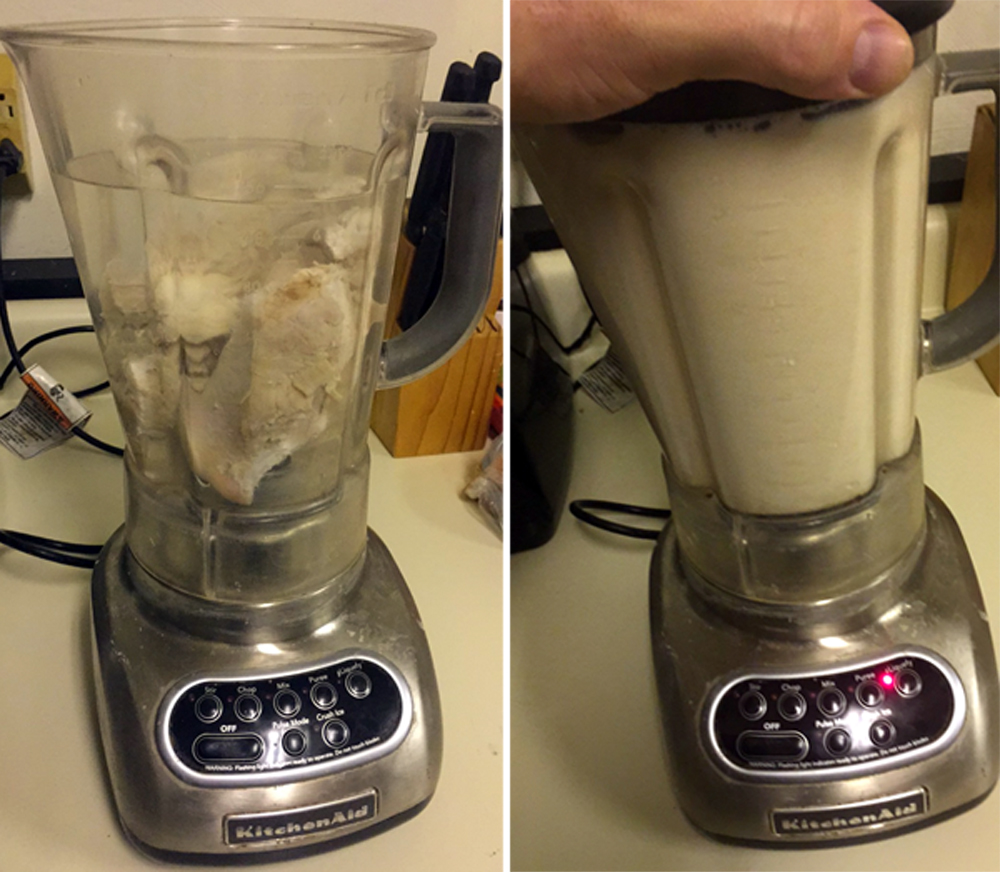

When it comes to my training, I don't just show up and happen to be able to perform. No one does that. I prepare for each mile marker target ahead of time. I eat enough. I sleep enough. I hydrate. The night before, the morning of; I run my mental game. By the time I get under that bar, I have already completed the task 1000 times. If I had any doubts about my ability to execute, they are gone before my first working set.

A huge benefit of training is the psychological reward we get when reaching short-term goals. There is a physiological aspect to this, too, but even without that, even when the goal isn't something physical, the psychological reward holds true. These "mile markers," in my case, can be as short-term as the goal for a given session.

Meeting a goal is fine, and that is usually enough to keep us going, but I prefer to set up short-term goals I know I'll be able to exceed slightly if I'm organized enough to prepare for them correctly. On the other side of the coin, there are usually psychological obstacles we need to face to meet even our short-term goals in training or any other aspect of life for that matter.

Performing well is, in itself, psychologically beneficial. No one feels great about doing an acceptable job or barely meeting the mark.

So, following a plan that allows for realistic "mile marker" goals like I mentioned above is a crucial piece of the puzzle. But also, we don't want to undervalue the role of psychological preparation in having the confidence we need to execute our plans and meet those goals.

Let me start my training overview by explaining that I rewrote this article in its entirety, after thinking through the way I presented the specifics of my current programming, which is complex and not explicitly relevant to the message I wanted to communicate. I did take the time to write those things out, as well as the templates I'm using for myself and a handful of variations of others I've been using with clients.

Again, that was wide of the point of this column, so I excluded most of it. For those who are interested, I may include these things in the second edition of Evolutions, which will drop on paperback on Amazon at some point in June (depending on the Apocalypse).

If you are familiar with my methodology, 5thSet for Powerlifting, you'll be familiar with the nine-day microcycle we use for it. If you are not well acquainted with the method, you can learn more about the nine-day microcycle here.

I'm still only training four out of those nine days: Two squat days and two bench days. Aside from activation work before each session, I am only doing SSB box squats and bench presses. That's it, and that's enough. Of course, I would not recommend this for a beginner or someone still in the process of basic development as a lifter. I have one high-volume session and one heavier session for each lift, per microcycle.

Right now, I am working with an 800-pound SSB training max, wearing single-ply with no straps (so basically briefs) and no knee wraps. The long-term goal is to squat 900 pounds in a meet, with wraps and the straps up. This seems doable for me, though it may take a year. That's a long time to pursue a goal, but micro-goals every session not only get me through the monotony of work, they also reassure me that I am on the right path and moving closer to my macro-goal all the time. My micro-goal for a volume session might be to improve or correct technique for every rep I perform on that day. My micro goal on a heavier session might be to maintain the improvements or corrections I made while using a heavier weight, or if tech is already good, it could be to get an extra rep or two with a given weight.

The take away from that brief synopsis of my current training structure, I think, is that I have a goal predicated on my ability to optimize the modifiable factors which influence successful performance. This keeps me accountable to prioritize those things because I am faced with the possibility of only performing acceptably or barely meeting the mark. And, as I said before, no one feels great about that. This incentivizes the work necessary to perform well while achieving my short-term goals. Performing well on my short-term goals becomes performing well on my long-term goal. Incremental improvement both "adds up" and is its own reward. It is truly the only path to anywhere worth going.

And that is the moral to extrapolate from our larger story this time, also. Set up short-term goals that not only incrementally support your long-term goals, but that remove as much misery from the process as possible.

Thank you for reading and, as always, please feel free to reach out with topics you'd like me to write about in future columns.

When it comes to my training, I don’t just show up and happen to be able to perform. No one does that. I prepare for each mile marker target ahead of time. I eat enough. I sleep enough. I hydrate. The night before, the morning of; I run my mental game.

I’ve been around long enough to have seen many seasons of fashion come and go in the sport of powerlifting. Some things become a trend and catch on because they are beneficial. More recently, as a result of various social media platforms, some things seem to have gained popularity because one or two highly esteemed lifters or coaches with powerful spheres of influence begin to do them. That’s right—in the second scenario, things become popular for the same reason clothing styles come into fashion.

RECENT: Optimizing My Travel Training Efficiency

Keep in mind that a lifter who respects or admires another more talented or successful lifter is likely to be open to trying the things that the more successful lifter is doing. It stands to reason that someone getting better results while doing something different from you could be getting those better results because of the different thing that he or she is doing. I see no issue with this logic so far. But let’s not pathologically oversimplify. We have to remember that many factors are at play in an athlete’s success or failure. For example, a big one is the fact that a lifter‘s ability to adapt to and recover from training is predicated mostly by genetic predisposition. It’s very easy to let our own confirmation bias get the best of us and convince ourselves that something is helping because we want to believe that it will. In this case, it would make us more like someone we revere. Functionality is not a requirement for that.

I’ll drag you on an embarrassing trip down memory lane here. There was a novelty rap group composed of two children in the early 90’s called Kriss Kross. These 12- to 13-year old kids dropped a music video in which they were essentially dressed with their clothes on backward. Backward jeans, jackets, hats, etc.

There doesn’t appear to be any functional benefit to wearing these articles of clothing backward. In fact, it probably makes your day a lot harder having all of your clothes on backward. The pockets are facing the wrong direction. Any time you put on a coat, someone else has to button it or zip it. It’s a bad deal all around.

And yet, it took almost no time for many other kids in my grade to start showing up for school wearing backwards pants, etc. I realize this sounds absurd, but I swear it happened.

This is a fairly solid example of a trend that defies logic. As a proposition, it makes things functionally more difficult and, in exchange for that hardship, seems to offer no functional benefit. There is an argument for an aesthetic value that could result in better social positioning. But I don’t think it’s a very strong one.

I think it’s safe to assume that no one puts his or her pants on backward under the impression that it would provide some functional performance advantage. This person has other reasons. In this case, the chief motive seems to be that it would set him or her apart from the current mainstream trend in a fashionable way. Again, dubious logic.

In the scenario with the popular lifter, it’s probable that we actually do imitate, perceiving that there is a legitimate performance advantage to doing so. But we should remember that there are other factors influencing that decision as well. Like, it’s fashionable, for one. Even if we are not consciously aware of that fact in the moment, it’s something we can do to either set us apart from the mainstream or draw us nearer to it. Both of which are compelling motives for similar reasons. Think mainstream vs. countercurrent fashion. (Think: wearing our pants backward.) There is also the obstacle of confirmation bias to consider, like I mentioned before. This is the psychological phenomena where humans will unconsciously seek evidence to support what they have already decided to believe and disregard or blind themselves to evidence to the contrary. This is a very realistic consideration when taking advice from an esteemed peer or personal hero.

Pausing in the squat and deadlift in various, typically troublesome positions, began to rise in popularity about four or five years ago. Prior to that, pausing wasn’t something you heard much about, outside of the bench press, probably because benches need to be paused in competition. However, it’s worth mentioning that the first person I knew of using them in the manner they are being used currently, even double pauses, was my fellow 5thSetter, Greg Panora, years prior to that.

MORE: What If No One Was Watching?

I have to say there is a decent logical basis for the theory that pausing in trouble areas could help to develop those areas of the range of motion for a given lift. However, when we pan back for a more holistic view of the proposition and think about the other factors for even a minute, the theory begins to dissolve in our hands.

They seem to teach you to slow down and to prepare to stop in the areas of range of motion that you never want to do either of those things. Some people do well with pauses. There is no question about that, but would they do better, as powerlifters, allocating those recovery and adaptation resources to something else? I think they would.

I base my opinion on the results of my own repeated experimentation with clients and that of other qualified and experienced coaches I’ve consulted. For example, the guy who invented the “double pause,” Greg Panora. I very slyly asked him what he noticed in his experience using pauses with his coaching clients and in his own training before I coached him, and his response was “They get slow.”

He isn’t wrong. I've noticed the same thing again and again—pretty much every time I'd put them in my clients’ programming until I finally eliminated them. This is why you won’t see them used on a single 5thSet template. Greg also remarked to me about an advanced lifter he coached, who put 40 pounds on a lift in six months after removing pauses. Bar speed improved visibly. This is not surprising to me in the least, because I’ve seen it with my own eyes, many times.

I have a few lifters whom I allow to pause their first four sets, but even in those cases, I do not want them to pause the AMRAPS, aside from resetting on deadlifts. There has to be some ballistic reversal in training the lifts to develop bar speed properly. Deadlift may be an exception to the previous statement, as that lift is about breaking resting inertia. So, repeated attempts to break resting inertia with as much speed as possible is probably a better plan. We do that.

But to address the underlying issue, if we don’t pause in these trouble areas, how on earth can we be expected to fix them? Well, I have a very novel approach. I develop lifters using a volume-based scheme where they will train the competition movement in the 70-85% range. This allows them to employ technical corrections using my cuing system for each lift. Yes, that’s right: my lifters develop the competition lift by learning to perform that movement correctly, meeting volume requirements in a given percentage range that satisfy the Prilepin chart. We don’t rely on “special movements” to develop “weak points” in the lifts. The lion’s share of work in training is performed as the competition lift, performed correctly and efficiently.

I don’t feel that I need to address the fact there is no apparent issue transitioning from not pausing in training for most of the year to doing so only at the tail end of a peaking cycle for a meet, based on the meet performances of my lifters, but I’ll go ahead and do that for the sake of thoroughness. There has been no apparent issue with making that transition in the literal hundreds of lifters I, myself, have coached into competition. With that much said, I remain open to the possibility there is a better way to do things. It’s just going to take more than an Instagram trend to convince me.

I hope you found this article to be helpful, or at least thought provoking, and I welcome you to reach out with ideas for future columns. As always, please share it and discuss this topic with as many different people as you are able. Thank you for reading.

More recently, as a result of various social media platforms, some things seem to have gained popularity because one or two highly esteemed lifters or coaches with powerful spheres of influence begin to do them.

For all of the negative aspects of Instagram, one unbelievably positive fruit it brings to bear is the ability for people like myself to offer a free Q&A session to their followers as a feature on their story. I’ve been doing this since the feature’s inception, at least a few years. Many other coaches and lifters on Team elitefts do the same on a regular basis.

Among the most common questions I get are those about my own training. Now, I typically need to preface any response with the clause: what I do is probably not what I would have you do. I live a crazy life. I’ve been in six cities in five different states in the last five weekends and on the road for 20 of the last 35 days. You can see how my needs and resources in terms of time, help, equipment, recovery, and a host of other factors may vary from yours. I’ve also been lifting for over 25 years.

That is not to say I don’t always run 5thSet, but my assistance work looks very different than most of the templates for the reasons I listed above.

For the sake of educational novelty, I will explain what my current assistance work looks like on the back work days, which are the second part of my squat and deadlift sessions. For those of you who may not know how 5thSet works, we use a nine-day microcycle model. Think of that like a nine-day long training week. Throughout those nine days, we have four scheduled sessions. We don’t schedule back-to-back days.

The deadlift and squat sessions involve a lot of heavy barbell work, and so, we will often split the session and do the assistance work, which is mostly back stuff, the following day. This is not a problem, as we don’t have back-to-back days scheduled, so it never overlaps.

These back assistance workouts are set up the same way in terms of framework. They are a series of exercises performed in rounds with no breaks between movements and a maximum of eight minutes between each pass. Failure with these is a different kind of experience. Sudden red-hot jabs of malfunctioning muscle will pull you under out of nowhere. These are performed for four rounds in both sessions. Both of these assistance sessions start with body weight pull-ups. The target reps are 15 currently. From there, the second movement is either a heavy row or a barbell throat pull off an incline bench with 10 target reps, depending on which session it is. The third movement is always a narrow neutral grip pulldown, also for 10 target reps. Fourth is cable or machine rows, also for 10.

Training this way is less expensive in terms of the resources I mentioned before, not the least of which is recovery. The combination of mechanical and metabolic stresses as stimuli remains effective enough for my needs while allowing me to do a tremendous amount of work in a short period of time.

I begin every single training session by doing my bracing/activation work, which is outlined in detail in Evolutions. This activation is also done in rounds but with no rush. That seems to be an easier way to move through things. And this way by the second time through I can “feel” everything working the way it should.

Keeping this activation stuff in my daily-use toolbox has allowed me to maintain a healthy spine, even after the catastrophic injury I suffered to it in 2014 when I dropped over 500 pounds on myself from lockout while bench pressing in a powerlifting meet. It also helped me be able to return to my strongest ever post-surgery. I had a double laminectomy and a discectomy and a root nerve relocation. Before this surgery, I was unable to stand or walk.

RELATED: How to Get Through a Near Career-Ending Injury

The lasting impact and profit from this ordeal came in the form of learning to develop a properly functioning system of muscles to support my torso by bracing effectively, and this made me a better lifter and coach. We have to remain grateful for lessons, even the difficult ones.

To outline everything more simply, after the bracing and activation stuff, this is what those back assistance sessions look like for me. I’ll add that anything involving the lower body from squat and dead sessions gets finished with the main work. These back sessions are pretty much all upper body work.

- Body Weight Pull-Ups x15 reps without letting go of the bar

- EZ Curl Bar Throat Pulls or Chest-Supported Dumbbell Rows (heavy) x10 reps, 2 count on eccentric

- Narrow Grip Pulldowns x10 reps to bottom of pecs, maintaining thoracic extension

- Cable or Machine Rows x10 reps to the lower torso

These are performed back-to-back with no breaks. Each pass-through is one round. For me, these sessions involve four rounds, but I’ve had them as high as five rounds at different periods. I mentioned before I take eight-minute breaks. This seems to be the sweet spot for this kind of stuff. Though I should mention, I usually feel like I’m going to die for about three minutes after each round, so for about half of those eight-minute breaks, I am probably lying on the floor. It’s alright; it feels good. As far as progressions go, when I meet target reps for all sets, I move the target reps up for the next time through.

When everything is said and done I do two sets of dumbbell curls with full pronation and supination on each rep. These are either sets of 10 or 20 reps, depending on which session.

I train this way when the demands of travel are high for a number of reasons. For one, it is sufficient stimulus to easily maintain my current level of development and inexpensive in terms of recovery. It’s extremely efficient in terms of time and the amount of work I can do. By being proactive, I am less likely to get injured from overuse while struggling to balance rest and sleep because I can more easily recover like this on the road.

I hope you’ve found this article helpful, and if you’d like to offer any ideas for topics for future columns, please feel free to reach out to me by any means. Except for coming to my house; please don’t do that.

With this training-while-traveling program, keep in mind I’ve been in 6 cities in 5 different states in the last 5 weekends and on the road for 20 of the last 35 days. My needs and resources in terms of time, help, equipment, recovery, and a host of other factors may vary from yours.

It’s no secret I spend most of my days traveling around the country, teaching 5thSet Seminars, spreading the gospel of specificity in the sport of powerlifting. I present on quite a few different topics at these events. But I would say the most popular, by far, is my Risk Factors for Injury presentation. That makes sense. No one wants to get injured, but I think there’s more to it than that.

My dear friend Sin Leung texted me this morning at an unthinkably early hour to share something she was told by her boss. This isn’t verbatim, but the gist of it was that while she was excellent at doing things correctly, the real value in her position was her ability to mitigate risk, and, when things do go wrong, her ability to solve problems efficiently. She attributed these skills, to some degree, to many years running 5thSet and traveling with me to seminars, learning the “hows” and “whys” behind the methodology which revolve around mitigating risk and solving problems efficiently, usually by preventing them.

RECENT: Motivation vs. Discipline

While I believe I am able to connect with my lifters well, at least for the most part, I’d have to say the real value of any coach lies with the same abilities she described about her own job. A lot of it is about sticking to the script. Trusting the things that have been proven to work well and prevent issues in the past. Heeding the lessons we’ve learned already. Taking a proactive approach.

For a coach, that should probably look like prescribing corrective technique cues and programming training in a range of intensity and volume that gets the job done, but also allows the cues to be effectively applied and reinforced. It sounds simple, but I’ve found this type of thoughtful approach seems to be more the exception than the rule.

This brings to mind a conversation I had recently on the Kabuki Strength Podcast with Chris Duffin. To summarize, we were exchanging commentary on our respective proactive approaches to handling injury with our lifters, that is to say, preventing it when possible and addressing the underlying causes, rather than simply treating symptoms if injuries do present themselves. I honestly went into that podcast with no preconception of how the experts at Kabuki do things, prepared for a civil exchange of ideas and opinions, which is something I truly enjoy, even when the opinions are conflicting with my own. By being open to new ideas or viewpoints, I am able to further analyze my own stance on things and so improve it whenever possible. It turns out we have pretty similar views on many topics, including the preference to break the mindless habit of the seven-day microcycle. I was surprised, in fact, to find that Chris actually uses a nine-day microcycle in his own training, much the same as we use for the 5thSet methodology.

Chris vehemently expressed his stance that most underlying causes of injury could be addressed before the fact, a point I think we agree on strongly. I went on to explain that there is a chapter in Evolutions, called Risk Factors for Injury, containing a lot of what I present about that topic in seminars. You know what they say about great minds. Well, they tend to be housed in the craziest people, for sure, but they also tend to think alike. At least, in the broad strokes — in this case, the way we look at problems. Yes, I’m referring to myself as a great mind.

The underlying theme here, put simply, is Proactivity > Reactivity. The former is almost always superior to the latter, but humans don’t seem to be naturally wired for it. It’s more of an acquired skill, in many cases. This is where a ranked hierarchy of priorities becomes crucial. When left to our own devices, our natural impulses tend toward the hedonic — the things that feel good in the moment (and profiteers know it). But this is problematic for a number of reasons. The things that feel good or things we expect to feel good in the moment very rarely translate into long-term fulfillment.

These short-term satisfactions in training look to me like a convention of little absurdities and horrors: taking a random max instead of following the scheduled plan, availing the lifter nothing substantive and possibly costing them dearly; taking increases greater than the increment prescribed, again, availing nothing beyond a momentary ego boost, and, again, potentially costing the lifter plenty. The manifestations of greedy, short-term thinking in training are nearly limitless, and often end in derailment of entire training cycles. This, for an Instagram video.

RELATED: 9 Things I Learned From a Social Media Detox

This behavior is not really surprising when we consider that beyond our own natural desire for short-term fulfillment, there is a modern cultural inculcation toward instant gratification. I’ve written and spoken a great deal about my opinions regarding the effect Internet platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat have had on our ability to rationalize with long-term, strategic thinking. This spills over on a small scale into our training, and on a massive scale, into impulsive sexually demonstrative behaviors and the way we address interpersonal relationships, even the way we conduct professional affairs. Whoever made the blueprints for these platforms, these roaring, glistening machines, could not have known the resulting cultural impact they would have. Right?

Or rather, they did know the short-term dopamine driven feedback loops created by these platforms could destroy the way our society functions and considered the temptation to exploit them for profit too great to forgo. Chamath Palihapitiya, former Vice President of User Growth at Facebook, admitted as much to an audience full of students at Stanford recently, conceding he felt “tremendous guilt” for the transgression.

Have you ever felt overwhelmed and anxiety-ridden when your phone died, and you realized you don’t have access to a charger? You might rationalize this response with thoughts about how loved ones may need to get ahold of you or come up with some other reasonable rationale for it. But I can’t remember ever feeling that way 15 years ago when my flip phone would die. Something to think about.

History has shown us there are few more spectacular means of departure for a society than its own hedonic technological advances. Ask the Romans. Yet, we continue the dance. But I digress, at least to some degree. Whatever the cause of the state in which we currently find ourselves, as a society, our ability to turn things around on an individual basis remains. The same way we have allowed ourselves to become conditioned, we can detrain and retrain ourselves; we can choose to view the consequences of our decisions from a macro, long-term perspective and reinforce positive habits or stick to a plan that considers the big picture.

In our training, we can be proactive and lay out long view plans of action. These should consider the many variables that affect our ability to adapt to and recover from training and our ability to express our current levels of fitness. Some examples of these are fatigue accumulation, risk factors for injury and specificity regarding desired adaptations. Essentially, all valid considerations are addressed within the 5thSet methodology. Read the rules and run a template. That is, by far, the easiest way to handle a thoughtful game plan for training and competition.

Regarding our personal and professional lives, I am unaware of any such template-based methodological approach to dealing with these issues. That would be nice, but it looks like we are each on our own in the fight to re-program ourselves. It’s a bit outside of my expertise, so I’ll stay in my lane. Maybe it’s not accurate to say we are alone. While the Internet causes many of these problems, it can also help to fix them, if we direct our focus the right places. Some of my favorites are Dr. Jordan B. Peterson, who has hundreds of hours of free lectures on his YouTube, and Jocko Willink, who wrote a book called Discipline Equals Freedom, which I highly recommend, and he also hosts a podcast discussing related topics.

READ MORE: The elitefts Article That's Changing My Life

I hope you find this information to be helpful. As always, please feel free to reach out with any idea for topics you’d like to learn about in future articles.

Try to keep an open mind when trying a new, proactive approach to anything, even if it doesn’t quite feel right at first — whether it be your job, social media, or a new program. Just because it doesn’t feel good right away doesn’t mean it won’t later on.

Motivation

If there is a single topic fitness personalities are asked about more than any other on social media — it’s motivation. And everyone who stands to make money from that concept is capitalizing on it. There are daily motivation accounts on Instagram dedicated solely to curating and posting poached sound bites on the topic from various well-known talking heads. Many people’s newsfeeds read like an endlessly unfolding tedium of pictures of motivational words as quotation. Whenever I ask for topics people want to learn about in my column, “how to stay motivated” is always at the top of the list.

Motivation is clearly in high demand. Business 101 tells you that someone or many someones are going to show up and cater to that demand, providing the things listed above.

RECENT: Top Three: A Hierarchy for Sustainable Success

The problem is these feel-good motivational memes and picture captions about “fighting the good fight” do little to actually modify behavior, that is, beyond the brief dopamine response when we read them and say to ourselves, “This is what I’ve been doing wrong! No more!” Returning later that day for another dose of this “motivation” seems to be the evident change in behavior, sadly.

We should think of our motivation as the deal we make with ourselves; our incentive, a kind of reward for the hard work we need to do. That’s what motivation really is: a motive. It’s our own unique “why.” Now, these are usually extrinsic things: the new car we want, maybe a new camera lens, some sort of praise or validation for our appearance or grades, or some other perceived accomplishment.

Intrinsic motivations are the motives we have for doing things that are internally rewarding. We may or may not get any praise for these things. Think about the difference between these two scenarios.

In Scenario 1, we consistently lift weights because it makes us feel much better while we are doing it.

In Scenario 2, we consistently lift weights because we want to beat a particular person at an upcoming powerlifting meet.

Now, clearly, in Scenario 1, the motivation is intrinsic; and in Scenario 2, the motivation is extrinsic. That’s not to say that we can’t have both, but as I described them above, those are the motivations. While it does feel good to train, it can be difficult to keep showing up when that is the only motive and often something we are not entirely conscious of. It may take us missing a bunch of training sessions to even notice we are suffering intrinsic consequences. That's if we are able to put cause and effect together at all, which, as I mentioned, sometimes we are not.

Extrinsic motivations can be helpful here. It is, after all, crucial for humans to have an aim or a goal to work toward, and simply “feeling better when we train” doesn’t seem effective for long. This is where things can get confusing. Extrinsic motives can be useful and good, but we can also receive too much of a good thing.

You see, intrinsic motivations can be shit on, believe it or not, when we receive too much of an extrinsic reward for them. That’s right, doing something we are internally motivated to do and internally rewarded by can cause a marked reduction in both of these if we receive too much of an extrinsic reward for that behavior. Less intrinsic motivation, less intrinsic reward. This is called the overjustification effect. It becomes purely work! The external reward, being so great, undermines the pre-existing internal motivation. The task itself becomes much less enjoyable.

So, we know we can’t go too far in one direction, but to be successful at any serious endeavor in the long term, we probably need a bit of both. The thing is, we are peeling a layer deeper into the onion than we probably need to. It’s sufficient to say that motivation is a fickle thing. Motivations may change, and they do, intrinsic and extrinsic, but the goals we are motivated toward rarely change.

RELATED: Implementing Self-Determination Theory in Coaching

All of this word vomit above; is this what you’re looking for when you ask about motivation? Probably not. Probably what you really want is the ability to complete the tasks you need to, whether they be training-, business-, or personal life-related. And what this boils down to is called discipline. Discipline rests a layer above our underlying motives.

Motivation is what makes us want to get something done. But most of us, truthfully, already have that, and still, we fail. Discipline is what gets it done.

Discipline

People tend to hate this word. Probably because it hangs on them, somehow, the blame for their own failures. They failed to reach their goal because they weren’t disciplined enough. I’ve certainly been no exception in that respect, but I do hold myself accountable.

Discipline, for many of us, brings to mind the idea of forcing ourselves to do things we hate. This is an extremely flawed way to view what is possibly the only path to true satisfaction and fulfillment for a human. At its core, this problem is about our desire for instant gratification.

Don’t believe me? Scroll on Instagram and observe for an extended period. You can even pick an individual and go to their profile and look back. Check out the posts they’ve made which got the most likes or interaction. Then compare those to the types of posts the same person made which garnered the least attention. Before long, these people are conditioned via dopamine response to an external stimulus, and their posting behaviors change to get the thrill of the instant gratification of that response. The brain doesn’t differentiate likes on the Internet from real-world compliments, even though it is highly unlikely we’d receive the same attention sitting in a Starbucks. Most people have no long-term plan for what they’d like to convey, and so, no plan or rules to stick to. Eventually, they will condition themselves to continue whatever type of posting or behavior will give them that instant reward.

Why do we drool when the bell rings? That means food is coming. Ask Ivan Pavlov.

As I write this, I know of many friends in the industry who publicly espouse discipline as a necessary virtue for success and yet consistently fail to demonstrate it in their own lives. After all, it’s no easy task to remain disciplined in the moment when things aren’t going our way. And who among us operates so far above their own ever-changing circumstances and reactive emotions that their discipline is never broken? Again, certainly not me, though, I am better now than I've ever been.

It needs to be said that I do know of a few who have conditioned themselves in this manner, and they are some highly effective individuals.

So, the question then becomes: How do we condition ourselves like those people have? This is a very complicated proposition because the biggest factor in someone’s potential for personal discipline may be genetic predisposition. That’s definitely something to consider, but it also sounds like an opportunity for excuses to be made.

LISTEN: Table Talk Podcast Clip — Why Strength Coaches are D-Bags

Much like genetic predisposition for potential to be successful in powerlifting, where we have little sway on our individual levels of recoverability and adaptability, we can still learn to maximize our ability to reach that potential. More or less, we always have the capacity to improve. This could put us in a much better position than we'd be in otherwise.

We can tailor our own behaviors to maximize personal discipline in the same way we can tailor our training, nutrition, and other factors to maximize our capacities for recovery and adaptation. It’s not magic, and in some cases, it can take a long time to manifest. But I believe doing so is the surest course we have to reaching our goals, whatever they may be.

The first thing to understand is we can’t be disciplined without a solid plan and a set of rules to follow. Without rules, we run the risk of becoming slaves to our own passions. Passions can feel really good in the moment. But a slave to passion is still a fucking slave. I don’t know about you, but I’ve done enough of that for 10 lifetimes, already.

So what do we do?

Set Clear Rules and Objectives

Like I said before, without a clear set of rules and goals, we run the risk of being led down the path of instant gratification. I’ve seen the end of that road, and I can tell you — it’s no place you’d like to visit. That’s not to say we can’t have reward systems in place that promote positive behavior, but this is not something that should be decided in the moment. We need a plan, and we need to stick to it by any means. We need to commit to these rules and this plan as our own code and take it very seriously.

Choreograph Behaviors

Discipline is about doing what we have to in order to reach a desired goal. We should decide which habits or behaviors are going to be conducive to that in the long term. We can set up the day like a routine or a choreographed dance and go through the motions consistently. Perfect practice, enough of it, makes perfect.

Analyze and Hold Yourself Accountable

This is maybe the biggest piece of the puzzle because if we don’t have the self-awareness to recognize when we have failed, we have little chance of avoiding the same type of failure in the future. Accountability, while sometimes difficult to maintain, can be a very liberating characteristic to develop. Right now, I am more accountable than I’ve ever been, but not as much as I’d prefer to be. Like all of these, this is a process.

When something doesn’t turn out the way we hoped, we should first look at what our own role was in that outcome. Did we fall short in any way? Was there some way we could’ve shifted our trajectory to a more desirable outcome? If the answer to both of these questions is “no,” we should probably reassess because we are heading toward the most dangerous type of crazy with that thinking: the type that sees itself as blameless for its own position.

READ MORE: Strength and Conditioning is Failing: Solutions to the Problems

That’s it; just three things. Progress may be slow and could take a good bit to manifest at all. That’s OK because we are each committing to our own code. This is how we are choosing to live our lives, to move in a direction that is positive and helpful for ourselves and those around us. No one is forcing us to do it. There are no cheat codes. No shortcuts. We have to chip away at this work every single day.

As always, feel free to reach out for topics you’d like to learn about in future articles and feel free to share this on your socials if you feel you’ve benefited from it.

Whenever I ask for topics people want to learn about in my column, “how to stay motivated” is always at the top of the list. Motivation is in high demand: you see it all over Instagram in memes, pictures, and captions. Despite the high demand, it sure seems like it’s in short supply….

Training is medicine for some of us. In this article, I am going to be speaking directly to the readers who fit into that category. Even for those of us who do, it may not always be easy to keep sight of the fact, though that does nothing to make it less factual.

For most of us, the volume of responsibilities we carry on our backs can make it hard to establish or even recognize our current hierarchy of priorities. It may seem the responsible thing to put training on the back burner. I can see how that might appear to make obvious sense. I mean, training is just a hobby. Right?

RECENT: Meet Report: 5thSet at the Kern US Open

Or, is it possibly something more? I can’t speak for everyone, but I’m happy to share my own experience on this topic, which seems to be in line with that of most people I coach. For me, training is a life-sustaining medication. If it came in pill form, it might be more easily accepted that I shouldn't miss a dose. But it doesn’t come in pill form. Maybe that is why its importance is so frequently undervalued. It’s not the highest item in my priority system, but as I’ve recently been uncomfortably reminded, it’s very close to the top of the list.

I try to cover the priorities talk with my lifters any chance I get that seems relevant, though I’ve admittedly strayed from it myself. The talk revolves around what I call the “Top Three.” Think of this as the medals-ceremony podium for priorities. If we keep these Top Three priorities in check, people like us are far more likely to sustainably function on a much healthier plane.

First, let’s look at how the Top Three should be structured, then we can get into some detail about how to define them, as well as the rationale which justifies their ranking.

- Family

- Work

- Training

The top priority should always be given to family. Work follows as a close second. And training should probably never move from the Number Three spot.

Many people identify training as a hobby, but, like I said in the beginning, I am speaking to those of us for whom training is medicine. For us, hobbies have to rank below training. This is a matter of mental, physical, and, most importantly, emotional health.

Now that we know the ranking for these priorities, we can take a look at what each of them actually means. There can be a lot of confusion regarding semantics, but we don’t want to let that get us off course.

Family

Family can refer to parents, siblings, spouses, long-term partners and in some cases, even dear friends we have accepted and ingrained as members of our respective clans. These are the people nearest to our hearts, the ones with whom we share our struggles and triumphs and labor to develop a healthy and sustainable interdependence.

“The goal is to create a compelling vision of what you and your family are all about,” Steven Covey wrote in his eye-opening book on the subject, entitled 7 Habits of Highly Effective Families.

Covey is a Harvard-educated consultant on the subject, and he is a big fan of single-sentence mission statements regarding a family’s unified purpose. His family’s mission statement is one of the most impressive I can imagine, and certainly one that speaks to my heart:

“The mission of our family is to create a nurturing place of faith, order, truth, love, happiness and relaxation, and to provide opportunity for each individual to become responsibly independent, and effectively interdependent, in order to serve worthy purposes in society.”

Whether or not your family culture and values align with his, the importance of developing a clearly stated purpose is an unequivocal game-changer in this department. Yours can look however you would like, but it should purposefully reflect the family culture you all agree you are trying to develop.

So this top priority, family, isn’t just about paying bills, or doing what other members want. It should be about adhering to a clear purpose you are all striving to serve together. This eliminates the possibility of the personal desires of one family member stifling the greater good of the whole clan, and instead allows us to lean on a system of values we’ve developed or agreed to together.

RECENT: For the Fathers and the Fatherless on Father's Day

People can have dramatically varying beliefs and values, so explicit communication and respectful compromise are often necessary. For us, it’s crucial to communicate the value and importance of our training to our families and integrate this into our system of values via compromise and mutual respect.

Work

While it is important to internalize responsibility for our professional identities, tensions between personal (family) and professional values usually cause problems. If Mom feels called to be a pastor, and Dad wants to pursue his dreams of joining the Thunder From Down Under all-male revue in Vegas, there may be some long-term trouble finding a sustainable compromise. This is part of the reason family stays above work.

Another huge reason is that if our professional lives cause us to lose our families, then we will end up in a worse position and the whole endeavor avails us nothing. I learned that lesson the hard way a long time ago. Family > Work.

Training

Sadly, this category is often viewed as a rather selfish one. However, if we look more closely, we can see that for us, it is actually a very powerful emotional and psychological corrective. Medicine, even. You wouldn’t stop taking antidepressant drugs you’d been prescribed because it got in the way of going to the movies or bird watching or some other hobby. So why would you ever not train to cater to one of these lesser priorities?

Let’s consider the type of person who decides to make physical training one of the top three priorities in their life. The rationale someone like that uses often relies on an instinctive identification of training as an emotional, physical, and psychological need.

The first thing I do in the application process when I’m interviewing a new client is to send them a list of personal questions to expound on.

I’ll give you a look behind the curtain here. The main questions I’m concerned about are regarding what got the lifter started training, followed immediately by what KEEPS them training. Any answer that doesn’t demonstrate a sincere need for training, tells me they aren’t really one of us, which need training in our Top Three. I can’t help those people. Their applications end up in the recycling bin.

There is a good amount of science to back up what I’m saying here.

Training can increase brain sensitivity for the neurotransmitters serotonin and norepinephrine. It can also increase testosterone and the release of endorphins in both men and women. All of these things make us feel better and operate with less anxiety, depression, and pain — even when we are not in the gym. Think about how much that could benefit someone who suffers from these conditions. Now consider how it can improve mood and interactions with loved ones.

READ MORE: The Monsters on My Shoulder

For us, this is not a selfish pursuit at all. We are better men and women when we train than when we do not. Better for ourselves, better for our families, better for our professions.

It can reduce our risk of chronic disease. It can increase the size of the hippocampus (part of the brain that affects memory and learning), increasing mental function in older adults. It can even reduce changes in the brain that cause schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease.

For people like us, training is medicine. We should prioritize and respect it as such.

As always, please feel free to reach out with topics for future articles in my column via my socials. Thank you for reading and please share this.

For some, training is just a hobby; but for others, training is much more than that. It’s what keeps me going, and it’s very close to the top of my list of priorities. But sometimes, we need to remember those other priorities, too. Here’s a reminder of what they are.

I had a 7:30 flight out of Pittsburgh International and very little sleep the evening prior. As soon as I pulled into the airport's extended parking lot, I mean the second the arm lifted so I could drive in with my ticket, it started to rain.

Now, the way Pittsburgh International is set up, to get to the terminal from the extended parking lot requires either waiting in a covered shelter for a shuttle bus (which may or may not come in a half-hour’s time), or committing to the 10-minute walk. I don’t know about you, but carrying a bunch of travel bags 10 minutes in the pouring rain, then squeezing onto a plane, soaking wet, for a six-hour flight, does not sound appealing to me. So I chose the uncertainty of the shuttle shelter.

RECENT: Training and Competition

Like a ray of hope on the horizon, the shuttle’s dim headlights broke through the dark, only moments after I’d dragged my luggage under the shelter. Mere mortals in the realm of travel, who only fly once or twice per year, will never appreciate the grim satisfaction that comes with those headlights, when they show up with time to spare. With that much said, I made it to the terminal without a terrible rush and even had time to buy a big coffee with some espresso shots for the flight. I’d eaten about 100mg of an edible herbal medication around the time of the headlights, which made for an interesting flight with all the caffeine.

I was wedged into a window seat, next to some teenage kid with poor hygiene and wandering eyes, trying to read what I’d type in my notes, constantly stealing glances at my iPhone screen. I covered the phone once with my hand and gave him a questioning look. He took my drift and was snoring before I knew it, but it was still a sub-optimal situation for a number of reasons. To be fair, I was already stressed out of my mind; and my emotional disposition was chaos long before we boarded the plane.

Still, I wanted to suplex this kid into the miniature toilet 10 feet from our seats. I thought better of the whole thing and played with my camera for an hour before giving in and purchasing Wi-Fi so I could work for the remainder of both flights. I was furious that I couldn’t bring Sydney with me. The extra plane ticket would’ve been too much. That’s a relevant factor in this. But I did almost get into a fistfight with the rental car guy, again. It doesn’t matter. I made it out with the keys.

And once I did step outside into the paradise that is Southern California, all of my anger slid through my fingers and I could not hold onto it any longer. I was happy.

© Erika Balasabas

My dear friend Alexander Cortes made the trip down to meet me at my hotel and we drove out to Ocean Beach. Mike’s Taco Club is probably my favorite taco spot on earth, so I never miss an opportunity to stuff my face there. This was no exception. The two of us filled our bellies with tacos and spent the day walking around, talking about life and how age changes us, as I took photos of all sorts of interesting things; from sea creatures to giant insects to puzzling architecture and antiques. That day seemed to be over as soon as it began and the coming three would leave me with little in the tank for myself. I was well aware of this fact. I went back to my room early and ate some microwave chicken and Life cereal from Target as I prepared the whiteboards for the seminar I’d teach the next afternoon.

The seminar itself went well as they always do. Gracie was kind enough to let me use her place. Everyone seemed to take a lot away from it, based on the conversation we all had toward the end. There were only around 10 attendees, throughout, but a couple of people who paid weren’t able to make it — so the cost of my trip was covered, even if barely. I set the seminar up in about a week’s time with the help of one of my lifters, Dan Clancy, and his friend, Jensen Kierulff. If I book a small seminar to cover the cost of my travel so I can coach my lifters in-person, I consider “breaking-even” to be a win. Because plenty of times I’ve had to come out of pocket to cover some or all of the expense of those trips. That’s business. I love doing the seminars and find them to be very rewarding. It all works out in the end, if you do the right thing, in my experience.

Now that I had the trip paid for, I could focus on helping my lifters: the reason I’d flown all the way from the other coast to begin with.

© Lorena Deanda

On Saturday morning, I met Dan and Jensen over at the venue for the Kern US Open, the San Diego Fairgrounds. I arrived around the time he got under the bar to take his first warm-up for squats. Dan battled his way through this meet to a very dramatic end. I can’t say enough how impressed I am with him. He’s been running 5thSet since before he did this same meet last year, and in doing so, was able to add a hundred pounds to his already impressive total. We ran into a couple of minor speed bumps, preparing for this meet, but everything came together on game day. Even if it wasn’t exactly how we hoped.

I would say Dan achieved a truly peaked state for this performance. He was healthy and free of fatigue, though he did go into this with an irritated bicep due to a strain caused by a technique issue. That bicep tore off from the distal end during his successful third attempt deadlift of 843 pounds, which locked-in a 2,072 total, a 100-pound PR. Somehow he managed to hold on and lower the bar under control with that tendon already visibly ruptured. It was one of the most impressive things I’ve ever seen, now knowing what was happening after watching the videos.

The 843 was the upper limit of the range for his third attempt, according to my formula. The second attempt of 788 looked like a warm-up and 843 would more than likely get Dan on the podium by 7.5 kilos.

© Lorena Deanda

And it did. He was able to take the podium and win money at the biggest meet in the world, competing against some of the best lifters in the world at his fourth meet ever. I’m proud to have him as one of my lifters and also as a friend. As I’m writing this, he’s already had the bicep reattached and is on the road to recovery. I see a long and exciting competitive career ahead for him.

First thing Sunday morning, my lifter and long-time friend Salina Vega finished squats with a 16-pound PR of 418 pounds. We had been back and forth about whether or not she would even be able to do the meet as a result of some nerve stuff with her back earlier in the year, which had been going on for some time. We seemed to navigate that pretty well, but her last pull certainly re-aggravated the same issue.

© Lorena Deanda

She held her own and carried herself like the professional she is; and I’m very proud of her performance. I am well-acquainted with the business of nerve pain related to the spine and hopeful this is something we can resolve by simply not loading it for an extended period of time, and also working on bracing exercises in the interim. This has proven effective for her in the past, and in many cases, in my own experience. Regardless, she is following up with the doctor and having imaging done, just to be safe.

The Kern US Open, as a whole, was an extremely impressive event, I’d say. And while there were a few minor speed bumps with the stage stuff, the meet was quite well-run and packed with performances I’ll not soon forget. There was also a bear, which was curious but satisfying. I wanted to experiment by putting someone in there with him to see what would happen, but then even more people would be mad at me. So I just left, grabbed a burrito and hit MedMen.

I was fortunate enough to be at the first US Open, however many years ago that was, coaching; and it was really cool see how far it’s come since that time.

San Diego is still my favorite place. Outwardly, all one can see is a human, writing and taking photos of things worth remembering; shrugging off specters of things worth forgetting. But I’m back at Keyhole in western Pennsylvania now, preparing for a summer full of seminars, meets, and other travels with the love of my life. I’ve never had it so good.

Header image © Lorena Deanda

Now that I had the trip paid for thanks to a seminar event, I could focus on helping my lifters at the US Kern Open: the reason I’d flown all the way from the East Coast to begin with.

If you’ve been at this awhile, you already know what I’m about to say. If not, allow me to provide you with some perspective. To those of you who have chosen to embrace the sport of powerlifting as competitors: you will have good meets and you will have bad meets.

That sounds like some common sense, right? It’s not a very complex proposition. I think we all know about good days and bad days. What I feel is understated within the sport, however, is the amount of sway the competitor actually holds on the kind of meet they have. When someone tells me everything was glued to the floor and they didn’t have the meet they wanted, my first question is always why they think that was.

“Just a bad day.”

As though bad days are simply dropped upon us at the whim of the gods. Fair enough, but if you don’t know why things went the way they did, they’ll probably go that way again, and sooner than later. I know all about bad meets, trust me. I see lifters having them all the time, and I’ve had a few myself.

RECENT: Returning From Injury After a Layoff

The panicked desperate weakness that lies in wait just a few inches from lockout; our own hard-earned muscle betraying us, denying us. The disbelief on our faces. The disgust. You might never see a lifter walk off the platform and look another human in the eye after missing a legitimate attempt. I think maybe I’ve seen it once.

It’s like we are all too ashamed or angry to interact with anything other than canned responses. Eyes are decidedly earthbound. We are probably not even capable of complex thought at that point and all communication is on autopilot. Those who would console us can’t reach us. The silver screens in our brains are all running the same film on repeat: a highlight reel of the lift we’ve just missed. If that was our last attempt, we could end up with an all-night marathon of that feature. Very entertaining.

We are mostly similar, really, powerlifters. It’s funny how many of us hate each other’s guts. But I digress.

Now, let’s get back to the part where I said the competitor holds more sway than we would probably expect. This is absolutely a fact. So, how does a competitor begin to tilt the scales in the direction of a good meet over a bad one? The first answer is accountability. Taking complete and utter ownership of our own performances. That is huge. The single biggest thing you can do to improve your squat is to be accountable for it, and the same goes for the other lifts and total. You have to compete in order to be accountable as a competitor.

But this is not an article about accountability. We’ve already done that one.

This is about the importance of understanding how different, but also important, training and competition are in their own respects. It is crucial to delineate these two as separate but mutually impactful things. If we looked at the vast majority of lifters who experienced the “bad meet” scenario, I’d be willing to wager they were doing a whole bunch of competition in training, leading up to the actual competition. In fact, they probably did better competing in training than they did on the platform. All so they could gaze winningly at the camera for Instagram, no need to even check for white lights. Let me help you out with a long form explanation of why this is a problem. Recognizing it as a problem is going to be part of the solution, too.

Training is where we do work; competition is where we get paid. Sometimes we don’t get paid what we feel we are worth, but we usually get paid what we’ve earned.

LISTEN: Is An Exercise Science Degree Worth It?

Sadly, as competitors, we never really get compensated in training. We get training PRs, sure. But they spend like McDonald’s coupons, and no one really cares about them except for us. We can post them on the internet and get loads of likes, but those same likers are going to love watching us miss those same lifts directly in the coming meet.

Hopefully, we are developing in a number of ways throughout the course of the training year. Platform PRs sometimes take a lot more than just strength training. Part of that is mental and emotional conditioning. For 5thSet lifters, only about 20 of every 100 sessions will involve going over 90 percent of their training max. The other 80 sessions will be about performing some type of volume-based program geared toward improving multiple characteristics that support maximal strength increases down the road.

Ideally, lifters will learn this lesson as beginners, but some late bloomers have used the 5thSet macrocycle model to learn to train effectively (without blasting gear), even later in life. I can tell you first-hand that it is a very liberating feeling, like learning to walk without a crutch.

So let’s start by looking at how training should be set up.

These are my current positions, my opinions. I’ve written extensively in books and previous articles about how I arrived at these conclusions and why, but there is not enough room to explain all of those here. Instead, let’s just define the two things and why they are important.

Training

The overarching goal in training is to develop the lifter completely. To develop their strength; their technique (movement efficiency, stability and consistency in execution); their psychology (self-regulation of peak arousal, self-confidence and self-control, and positivity and focus toward challenges): all of it. All of these capacities are developed in training, though many are best expressed in competition.

This is accomplished throughout the year by putting greater or lesser emphasis on developing the various characteristics needed to consistently execute in competition. I think the secondary emphasis in training should probably be rotated based on some premeditated logical sequence, where each mesocycle puts special focus on a characteristic which will benefit the subsequent mesocycle’s objective.

For example, if I was writing a 5thSet program, the secondary training emphasis might be on hypertrophy for the first two mesocycles and then shift to a more pure strength stimulus for the next one. This would probably be followed by a peaking mesocycle, which would ideally start around 44 days out from competition.

In the peaking cycle, the stimulus would be very specific to the demands of the coming meet. The main work would be mostly singles in the 90 to 100 percent range to just beyond the first half of the cycle. Then, in the second half, the goal would shift to reducing fatigue as quickly as possible while preserving the capacities and characteristics developed throughout the training year. This reduction will hopefully allow the lifter to accurately demonstrate their strength without any inhibition caused by excess central fatigue, while at the same time mitigating the risk of injury in competition.

RELATED: Your First Meet Cycle — How to Lay the Program's Foundation

Regardless of how training looks prior to that peaking cycle, if the lifter continues to try for PRs too far into the second half of that peaking cycle, chances are they won’t have enough time to be fully recovered or free of central fatigue in time for their meet. This usually leads to performances on the platform that are less than they were in training and at an increased risk of injury. Not a good deal.

Training allows us to analyze and make corrections or improvements, which are not possible in competition. Thinking while performing a max in competition doesn’t usually work out very well. The movement should be thoughtless by then, after all of the training we've done. This is part of why internal cues can have a negative impact on performance in competition. The thinking slows us down.

In fact, I’ve had a hard time getting anyone to effectively implement corrective technique cues with more than 83 to 85 percent of 1RM in any scenario. This means integrating technical cues is probably going to be extremely difficult, if not impossible, while lifting over 90 percent. However, strength can easily be developed in the 70 to 85 percent range. So while training in that higher range may be necessary as we approach competition, we can see how doing so the rest of the year could become counterproductive. This seems especially true when we consider that technique tends to decay over time when it is not monitored and reinforced, especially as more fatigue is accumulated.

So what about competition?

Competition

From what I can see, the trending overarching goal in competition seems to be to fail on the platform with the heaviest weights possible and to do this as often as possible for as long as possible. (Hint: it’s not very long.)

At different periods in time and even in certain special cases today, lifters have concerned themselves with actually winning a meet against other competitors. I know this sounds impossible with 150 different divisions and weight classes in each meet, but the big ones do actually force you to “compete” against other qualified lifters.

I’m persuaded that the overarching goal in competition should be to build a progressive and robust competitive history that spans a long enough period to develop completely. If we are not allowed enough time and experience to develop completely, if we destroy ourselves first in the process, it doesn’t matter how quickly we improved for a time: we will never reach the heights of strength we would have if we had been smarter about things.

Competition itself is a very important aspect of that. It forces us to structure and prioritize our training because we know we will have to deal with our own performances. That’s not the same thing as being accountable, but it’s a step in the right direction. At least, it sets us up for a learning experience albeit with no guarantee we will actually learn anything, as we’ve already covered. Many of us are all too familiar with these fruitless “learning experiences” to even deny that. But we can choose to be humble, to be teachable. If we do that, we can learn a lot from competition; potentially, how to avoid more long nights with visions of failed attempts dancing in our heads.

READ MORE: How I Trained for a 600-Pound Bench

Competition should allow us an arguably safe environment to hit the heaviest numbers we’ve ever lifted. A well-run competition provides competent spotters, some potentially life-saving safety devices, and top-notch equipment, including bars and even calibrated plates.

This may seem like the ultimate opportunity to see what we are capable of, maybe hit some lifetime PRs, and cash in on all the intelligent work we’ve been doing in training. It can and will be that if we learn to identify it as such. It will almost certainly not be that if we treat every session in training as though it were the same opportunity.

It is crucial to delineate these training and competition as separate but mutually impactful things. I’d wager that the majority of lifters who had a bad meet were doing a whole bunch of competition in training, leading up to the actual competition.

If you know anything about me, not much of what I say here is going to come as a surprise. I am a “plans” guy. I strive to be intentional and methodical with just about every action I take — premeditated, even. Except for any role played in someone’s death, of course. That would have to be the result of an unavoidable accident of some kind and not at all premeditated. Theoretical circumstance and knee-jerk reactive social situations aside, most of what I do is premeditated.

So it stands to reason, whether I am returning from injury or helping someone else with the process, I’m going to put together a long term strategy and plan of execution. I’m not a doctor. I’m not a physical therapist. I am a coach and lifter with a nice amount of experience with what comes after the doctors and physical therapists are out of the picture. I can’t put together individual strategies for all of you, but you can take the initiative using some fairly simple principles as guides.

RECENT: Powerlifting Meet Manual (with Formula for Selecting Attempts)

Before I lay out the three big principles I have to cover, I want to touch on some other things to consider. Last week I asked for some personal experience on this topic from other lifters and coaches on my social media. I’m limited to some degree, but I’ll include a few interesting points which were made by the respondents.

There are some positives if we play our cards right. Sometimes a hiatus from training isn’t such a bad deal. On the short term, it sucks, but if you’re playing the long game, a layoff can present some rare opportunities. For example, rehabbing after being cleared by your doctor is an opportunity for re-education but this can definitely be a double-edged sword. Coming back after a layoff can be a chance to address imbalances you’ve been putting off, but it also presents the opportunity for new imbalances to develop or even worsen if we aren’t careful. It makes sense to pay special attention to this aspect if that’s what caused the injury in the first place.

It’s a period that can be used to improve other lagging areas that are not affected by the injury, but it’s also a time when people tend to do some really dumb things in their training. Muscle memory is definitely a thing, and strength tends to come back quickly. As a result, for many lifters, testing becomes a normal and frequent ordeal. Common sense tells us constantly testing our strength after a layoff from injury might not be the best idea. But we will get into that, or more accurately, how to best make decisions about training in these circumstances (that is: way ahead of time).

The number of possible injuries that can put a lifter out of training for an extended period is ridiculously long, and there’s no way I could address them all. Nor can I talk about the best specific course of action in returning for each individual case. The best I can do is offer a few principles to help decision-making in this arena a smoother process across the board.

Have a Solid Plan and Stick to the Script

Have a plan and stick to it, even when things are going well. Especially when things are going well. If I could choose one piece of advice for you to take away from this article, it would be what you just read.

If we take a look at the problems lifters run into when returning to training after a layoff due to injury, we will notice a single thread winding through the entire ordeal: common sense. Or rather, most of these problems could be avoided by employing common sense in decision-making. Why do we struggle with that so much? Usually because we haven’t embraced any solid construct that prevents impulsive decision-making. Laying out a solid plan of action ahead of time can go a long way to help us avoid giving in to impulsivity.

We may be able to make good common sense judgments, planning things out ahead of time, but we could also choose to make entirely unrealistic plans for our return. It may be a good idea to run your plan by a few trusted people with experience in this realm.

Low and Slow at First

Of course, we all want to go back to training after an injury like nothing ever happened. Most of us feel like we have suffered enough, emotionally and psychologically, during the layoff from our passion. After being cleared to train, we are understandably excited to get back under some heavy weights and feel like ourselves again. However, if we head directly for that destination, we are probably going to end up compromising the recovery we’ve made and eventually backslide. This could be a result of either the same injury, which put us out before or something new related to compensation. I've dealt with both.

RELATED: Troubleshooting Strength Injuries: What is Autoregulation?

There is another sort of weakness that comes from any extended hiatus from the iron. That is perceived weakness or insecurity. The internet lets me watch plenty of this in real time, but I’ve seen my fair share over the years from lifters I’ve worked with as well.

It’s a combination of the perceived and actual loss of strength, though the latter tends to be outweighed by the former. This insecurity may account for the heaviest aspect of returning to training after an injury.

“Can I still lift this?” The answer is: not right now. It’s worth mentioning this is a problem I recognize plaguing lifters of every skill level, regardless of injury status, adjusting training based on mood or current emotional state. Bad business.

“I just want to feel the weight for confidence.” Imagine if being confident under heavy weights didn’t matter at all during this phase. Imagine if your best bet was to follow the intelligent plan we already discussed lying out (before touching a bar). Now accept that both of those are true most of the time, regardless of the injury you’re coming back from.

But one might expect with a still-recovering injury present, it would be obvious starting back slowly is the way to go. I mean, common sense, right? If you’re reading this, you’ve probably spent enough time in the weight room to know common sense is decidedly less than commonplace in there. The blood gets pumping and we begin to lie to ourselves about our capabilities. This is the land of testosterone and impulsivity.

Which is why having a solid plan and sticking to the script is the single most important principle for recovery. I’ve come back from various surgeries (even a serious one to my spine) and more torn muscles and nerve issues than I could possibly count, and this is the short list. Recovering from each of those was a long, harrowing process. Yet I am able to lift and live my life without nerve or back pain of any kind, and most of the muscles I’ve torn are working as well as ever, with the exception being my missing medial delt, whose performance has been underwhelming, to say the least.

How did I pull this off? (The recovery, not the medial deltoid.) I stuck to the script. Plain and simple. Even when I didn’t want to, I stuck to the script in every respect. I started back training below what my abilities were at that time, meaning I did far less than I was able with the affected muscles or areas every step of the way, focusing on proper movement rather than heavier loads. I did not allow myself to move poorly or fight through pain to lift heavier weights. As a result, I was able to lift heavier weights again without pain and without re-injuring myself 97 times.

It’s crucial to keep in mind a full recovery can take more or less time depending on the nature of the injury and the capacities of the lifter. My spine injury and the resulting surgery changed the way I will be able I train for the rest of my life. But that notwithstanding, it took me almost three years to get back to where I was before the injury in terms of poundage.

Nearly every success story shared with me, after I posted on my socials asking for personal experience, mirrored something similar to the point I just made. Some people seemed to beat their heads against the wall at first, but the overarching takeaway was universal. In order to recover, things have to change and the ego has to go.

WATCH: Table Talk — Bicep Tendonitis with Dave Tate and Joe Sullivan

My brother, Vincent Dizenzo, laid it out fairly simply. I’m paraphrasing here, but he said something to the tune of the following: If a lifter tries to come back from an injury after a layoff by training at the same level he was when he left, it’s going to work out about as well as a former heroin user starting back with the dose he was using when he quit.

That’s an apt comparison.

Use Your Pain

Pain can be a useful tool. Throughout this process, we should use it as a guide. It’s our bodies’ way of saying “hey, don’t do that,” almost always.

There are different types of pain, sure, but the kind of pain we experience from being injured is a little different than normal training pain. We know, almost instinctively, the former type of pain is a sign something is wrong, while the other is a sign things are right. As a rule, I personally have followed my own recovery plans to the letter, right up to that point of pain, even just marginally beyond it. But no more. In other words, I do not attempt to “train through” pain or anything like that while recovering from an injury. Ever.

Intelligent application of this principle can make a night and day difference in the outcome of our comeback strategy.

As always, if there is any topic you would like to read about in future articles, please feel free to reach out. And if you found this helpful, please share this on your social media.

Coming back after a layoff can be a chance to address imbalances, but it also presents the opportunity for new imbalances to develop. Common sense suggests that testing strength after a layoff isn’t the best idea. But if you are going to do it, keep these things in mind.